This article is the second in a two-part series looking into redistricting in New York City. First, we looked into the history of redistricting. Here, we examine the Unity Map, proposed by a coalition of voting rights advocacy organizations representing people of color in NYC.

Communities across Brooklyn voiced their concerns on Tuesday about the proposed state Independent Redistricting Commission’s (IRC) competing electoral district maps, which were supposed to be bipartisan and compliant with constitutional principles of fairness and equality.

On the eve of the hearing at Medgar Evers College, Central Brooklyn residents gathered in person and virtually to share their opinions about the IRC maps.

Assemblymember Stefani Zinerman hosted the Bedford Stuyvesant and Crown Heights Committee on Fair Redistricting meeting Monday night for her predominantly Black Assembly District 56.

“We’re looking at these maps today because the committee looked at the two maps presented by the IRC and we rejected those,” Zinerman said.

“We did not think that those maps reflect the values of our community or contain assets that we want to keep in our community. And so, we went through the process of developing our own maps.”

Residents were given the chance to vote among several proposed maps the committee created.

They also considered the Unity Map designed by the Unity Map Coalition, a trio of voting rights advocacy organizations representing people of color in New York City.

Sunset Park and Bensonhurst

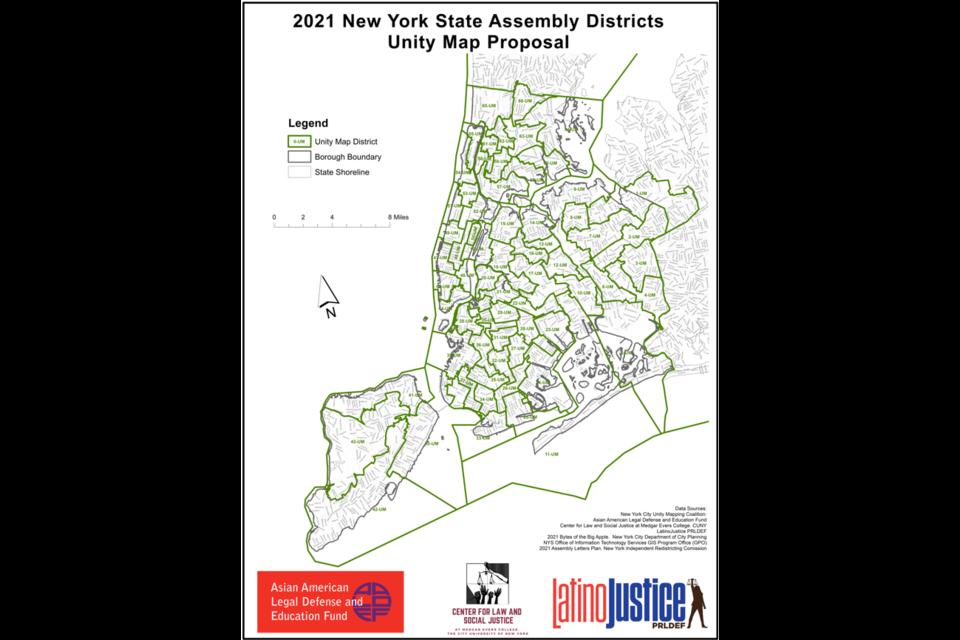

On Nov. 4, the Unity Map Coalition unveiled its proposed redistricting plan for the city.

The group is comprised of LatinoJustice PRLDEF, the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) and the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College.

Sen. Zellnor Myrie’s Senate District 20 is an example of what’s wrong with the current map that must change, AALDEF’s Democracy Program Director Jerry Vattamala told BK Reader.

The district is centered in predominantly Black neighborhoods that include Brownsville, Crown Heights and East Flatbush.

But it also includes Sunset Park, which is predominantly Asian.

“They don't share many things in common, and they're geographically not even close to each other. In terms of communities of interest, they don't share many things in common with those other communities in the district,” Vattamala said.

State Senate Republicans created the district 10 years ago when they were in the majority. That configuration dilutes the voting power of Sunset Park's Asian residents, as well as the collective voting power of Asians across Brooklyn.

AALDEF proposed a district map that places Sunset Park and Bensonhurst in the same Senate district. They both have a large population of Asian residents and are located in close proximity. This would also enable Asian Brooklynites to elect an Asian representative to Albany.

Vattamala said right now, Bensonhurst is “sliced and diced into multiple state Senate districts.”

“The problem with having your neighborhood in three or four different districts is that all the work that a lot of groups do on voter registration, getting out the vote and census all go out a window, and they are unable to elect the candidate of their choice,” he stated.

The coalition’s work isn’t a zero-sum game that pits the interest of one community of color against the others, Vattamala stated. The coalition arrived at a consensus on the maps through a give-and-take process.

Silent voter suppression

“Redistricting is often the silent voter suppressor,” Fulvia Vargas-De León, a lawyer with the LatinoJustice, told BK Reader.

There's a lot at stake for communities of color in the redistricting process.

“We stand to lose representation and the ability to have elected officials and districts that are reflective of the needs and demographics of a community,” De León added.

For three decades, the coalition has voiced concerns about a redistricting process that has too often produced electoral districts that diminished the voting strength of Asian, Black and Latino communities.

“Redistricting is not an out-loud process, and as such we don’t see its detrimental effects until members of our community attempt to exercise their right to vote,” De León said. “Once these maps are adopted by our legislature, our communities become bound to these maps for an entire decade.”

Accuracy counts

The coalition demands districts that accurately reflect population growth and locations of communities of color, CLSJ Executive Director Lurie Daniel Favors said at a press conference.

Favors explained that the Unity Map aligns with data from the 2020 Census, which showed that Brooklyn is the most populous borough, with a significant increase of 45% of the Asian population.

At the same time, CLSJ is advocating for a reanalysis of the 2020 Census, which found an 8.7% decline in Brookyn’s Black population.

A CLSJ report disputes that finding based on the Census Bureau’s failure to identify the full spectrum of people of African descendent as Black.

Meanwhile, other efforts are underway to ensure voter equality. Sen. Myrie has spearheaded legislation to address infringements on voting rights through his John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act of New York. Named for the late civil rights champion, the legislation includes tools to fight voter suppression and vote dilutions that are stronger and clearer than federal protections.