A new exhibit at the Center for Brooklyn History delves into one of the borough's long forgotten and unspoken history: its ties to slavery.

Trace/s, on view until Aug. 30, weaves together powerful artwork and historical records to play tribute to contemporary Black genealogy researchers, offering a deep exploration of Brooklyn's complex past while honoring the work of those revealing its legacies.

“The story of slavery in Brooklyn is not one many people know about,” said Natiba Guy-Clement, director of Special Collections at the center. “People often associate slavery with the South and overlook its presence in the North. There’s a misconception that the North didn’t have slavery, or that it was less oppressive, but it did exist. It happened here, and it impacted Brooklyn families.”

While firsthand testimonies from enslaved people in Brooklyn are scarce, the center’s special collections offer valuable insights into their lives. Trace/s invites visitors to confront how the institution of slavery built the Brooklyn we know today.

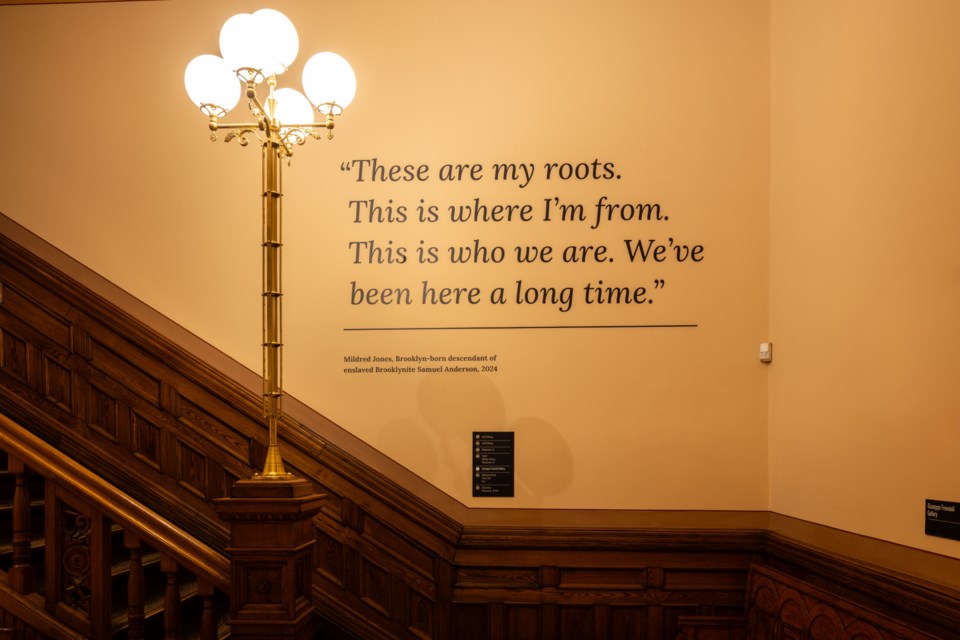

At the heart of the exhibition are two portraits: John A. Lott, a member of one of Brooklyn’s most prominent slaveholding families, and Mildred Jones, the great-granddaughter of Samuel Anderson, who was born enslaved to the Lott family and freed after New York’s 1827 emancipation. While no photos of Anderson survive, the exhibition features a portrait of his descendant, Mildred, as a powerful visual connection between the generations.

“Often, we see portraits of prominent figures with streets named after them, but we don’t hear about the people their families may have enslaved—the individuals who helped build their wealth," Guy-Clement said. "So, we looked at the story through the lens of both John Lott and those he enslaved, and with the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, we were able to identify a family enslaved by the Lott family."

For every name in historical records, countless others were erased, omitted, forgotten or deliberately ignored. Trace/s confronts these silences, reclaiming the lives of those who built Brooklyn but were denied recognition. The exhibit reminds us that history is not just what is preserved—it is also what has been deliberately left out.

Lott and Anderson were born just seven years apart—one into power and privilege, the other into bondage. Their intertwined histories underscore the importance of genealogy in uncovering narratives often excluded from traditional records. Trace/s showcases the work of Stacey Bell, Lynn Huggins Smith and Muriel Roberts, genealogists from the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, who traced Brooklyn’s enslaved and formerly-enslaved population by piecing together fragmented historical documents.

A dedicated section of the exhibition reveals their detailed research process, from deciphering handwritten census records to using DNA testing to restore lost family connections.

In addition to the exhibition, the center is hosting a range of programs, including genealogy workshops, film screenings and panel discussions. High school students can apply for the Summer Scholars internship program, which provides hands-on experience in archival research and a deeper understanding of Trace/s.

“For every exhibition we create, it’s always about sparking curiosity,” Guy-Clement said. “We want to ignite that spark so that when people enter, they think, ‘I didn’t know this, but I want to know more.’ It’s an invitation to learn, to understand the archive, and to explore how your own story connects to it.”

Trace/s is more than just a reflection on history—it is a call to action. The exhibition challenges us to reflect on how the past shapes our present and how we can move forward with a deeper understanding of who we are and where we come from.