Russell Frederick was 27 years old and working as a hospital clerk when he announced he was leaving the field of healthcare to pursue a career in photography.

His family scoffed at the idea: His mother pleaded with him to change his mind, calling his interest in photography a "hobby," not a career. His grandfather, who had immigrated to Bushwick from Panama a few years before Russell was born, said, "You think we came to this country for you to take pictures? That's not why we came here "

Even a doctor at Beth Israel, where he had worked for the last nine years, said, "Russell you're way too smart to do that." She offered to pay for his nursing school.

But Russell had already made up his mind, and this time, he was prepared for the push back. Since the age of 12, he'd been fighting the same battle over whether to show his authentic, creative self or continue living out the dreams of others.

"My mom used to complain, because, as a child, I used to doodle all the time when what she really wanted me to be doing was reading a book," said Russell. "Honestly, when I would draw, I really didn't know what I was doing or why I was doing it, I just knew I enjoyed it so much It was a discovery phase for me."

Eventually, his mother banished him from all of his art supplies. That was a mistake: Russell got even more creative and began making his own markers by emptying roll-on deodorant bottles, filling it with rubbing alcohol and carbon paper. He let the carbon paper soak for a few weeks, "borrowed" chalk board erasers from school, peeled off the wool, folded it over the roll-on bottles, and voilà: markers!

With his new markers, he got into graffiti art. "That was during the 80s when graffiti was public enemy #1," said Russell. Eventually, he was stopped by the cops. And that was the breaking point! His mother, a nurse, got her son a job working with her at the hospital where he could begin a viable career in healthcare.

Surprisingly, he enjoyed working in healthcare. He enjoyed helping people. And he was intrigued by the human body. But he found the work environment stringent, sterile, political and eventually, he began to feel unfulfilled.

He picked up his first camera at age 26 when some friends from church asked him to style and photograph the fashion section of their new magazine, Indigo. It was fascinating, capturing the beauty and innocence of real-life scenarios. Suddenly, his creative compunction re-surfaced— this time, stronger than ever.

Russell enrolled in an introductory course in black and white photography at the International Center for Photography. The first day of class, the instructor at ICP, the late Bernard Palias, noticed Russell's work and told him he would be a great photographer:

"When he told me that, I just never looked back," said Russell. "I realized what I was put here to do."

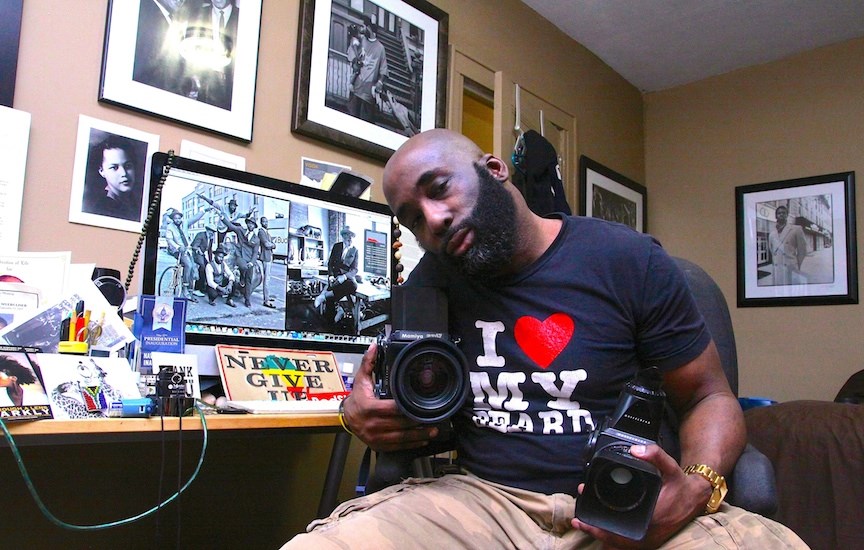

Photo: Russell Frederick

Russell announced to his colleagues at the hospital that he was leaving to pursue a full-time career in photography.

Shortly after, a buddy of Russell's introduced him to a neighbor named Eli Reed, an older gentleman, who his friend noted, "always got a ton of photography magazines in the mail." Little did Russell know that Reed was a well-known photographer— in fact, the only black photographer at Magnum Photos.

"Reed was always traveling," said Russell. "He'd been to Beirut, all over the world. And he was the first to give me really good feedback on developing my portfolio."

Eventually, Reed became Russell's mentor and saw such promise in Russell's work, he was able to secure for him a job at Magnum in the traffic department where he began handling the film, prints and contact sheets of all the photographers in the NY bureau.

"I got to see all of the photos first," said Russell. "I learned the business side of things. I started developing my photographic IQ. In some ways, I think it was even better than an education at NYU or SVA."

In 2000, he was accepted into a special photography workshop program in St. Louis, called "Diverse Visions," where his work was noticed by Fred Sweets, senior photo editor at The Associated Press and Vin Alabiso, vice president of photography at AP. This relation led to him getting a job in the photo library department at AP, where he would work for the next eight years.

Photo: Russell Frederick

Around this same time, Russell began to notice something about his neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant:

Street lights were being disassembled and switched to cast iron. A few weeks later, he noticed that Fulton Street, between Bedford and Marcy, which used to be thick with street vendors, was empty. One day he came out, and they were gone.

"Once I saw that, something said to me there's some changes going on that not everybody is aware of So I went to a community board meeting and they said it too. The community was changing, and they predicted in ten years that a studio apartment in Bed-Stuy was going to be $1,000. At the time, I was paying $425 for my studio.

"That sealed it for me. That prompted me to aggressively begin photographing the community before its total transformation," said Russell. "Also, whenever I told people at work that I lived in Bed-Stuy, they would cringe and laugh and say, 'Oh, you must walk around in a bullet-proof vest and a helmet.' And I was offended, because I knew what I saw, and that wasn't my experience."

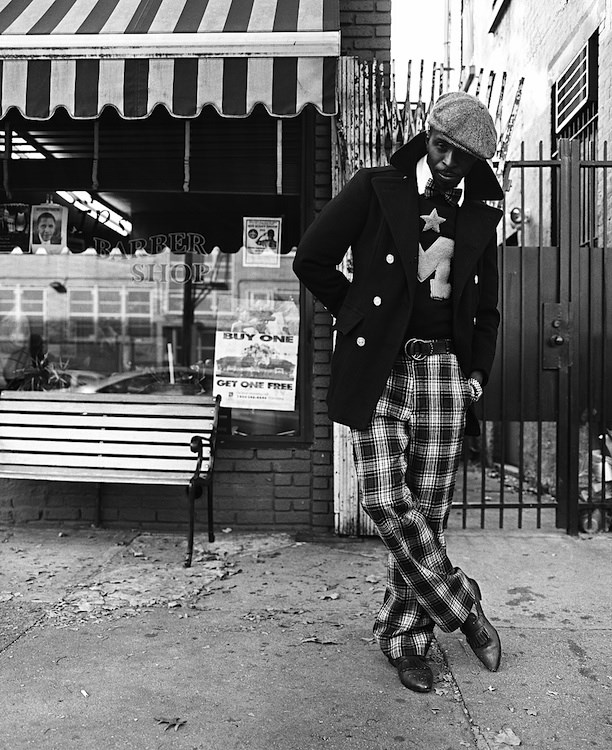

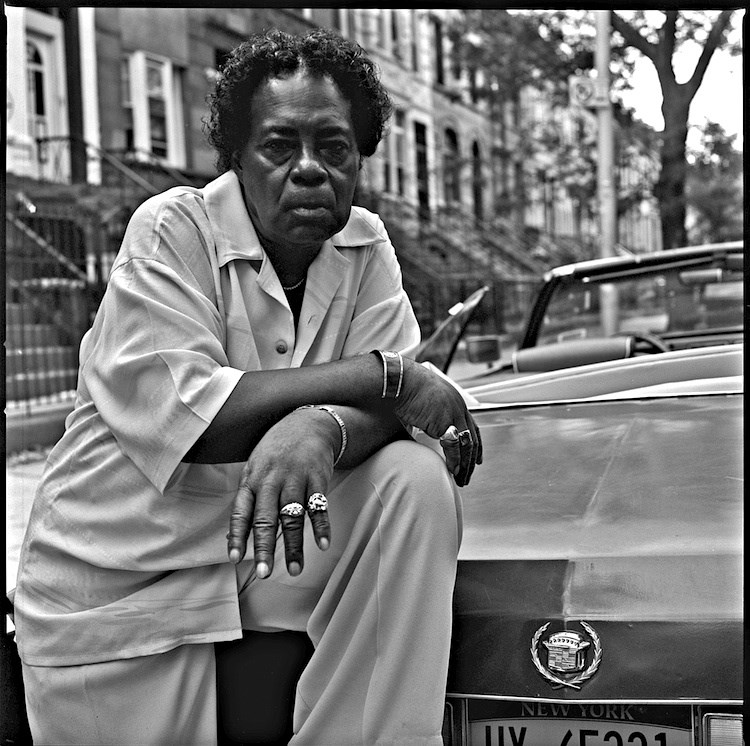

Photo: Russell Frederick

"People on the outside only saw our challenges, but not the diversity, the love and the heart and the soul of the community. I realized that the community needed honor; the pioneers needed to be honored; the people's voices needed to be heard.

Photo: Russell Frederick

"There were a lot of untold stories for the place that was home for me, because the people who weren't actually from Bed-Stuy or even Brooklyn for that matter, were telling our stories," he said.

Photo: Russell Frederick

"I felt the best way to author an accurate story would be visually. And it was from that point on, I started photographing Bed-Stuy with a purpose."

It's been 15 years that Russell has been documenting Bed-Stuy. All black-and-white photos, in medium format, using a Hasselblad camera in gelatin prints and developing them in a dark room, old-school style.

"This work is my life purpose; it's personal. Because I think the images that exist for us need to be challenged, and the image that we have of ourselves needs to be challenged." said Russell. "But it's not all sugar either. I photograph our challenges too. But it's done with respect and honesty, so that even when [the subjects] look at themselves, they are looking in a mirror in a way that they either feel proud or embarrassed and might want to do something about it."

Photo: Russell Frederick

His Bed-Stuy photo library is now a massive collection of more than 1,000 images, all of which are being compiled for a book. He's looking for the right publishing home now. But in the meantime, his work has been recognized and currently is exhibited all around the world— everywhere from Australia to France, from Ghana to Poland, from Italy to Holland.

Photo: Russell Frederick

Russell said that one of his proudest moments was when his mom went to China for a show he had there.

"She came out to my show in China!" said Russell. "And I can't tell you, that was a huge personal, spiritual battle for me. When you are on your own and you're trying to figure out your purpose while honoring your family who were immigrants."

"Now, my mom is my number-one fan."

He shakes his head and looks out of his bedroom window. And smiles.

To see more of Russell Frederick's work, visit his website.