A decade after suffering injuries at the hands of NYPD officers that left him in need of surgeries and physical therapy, a civil rights activist and former city aide has become the face of a push to get New York lawmakers to reform the lawsuit lending industry.

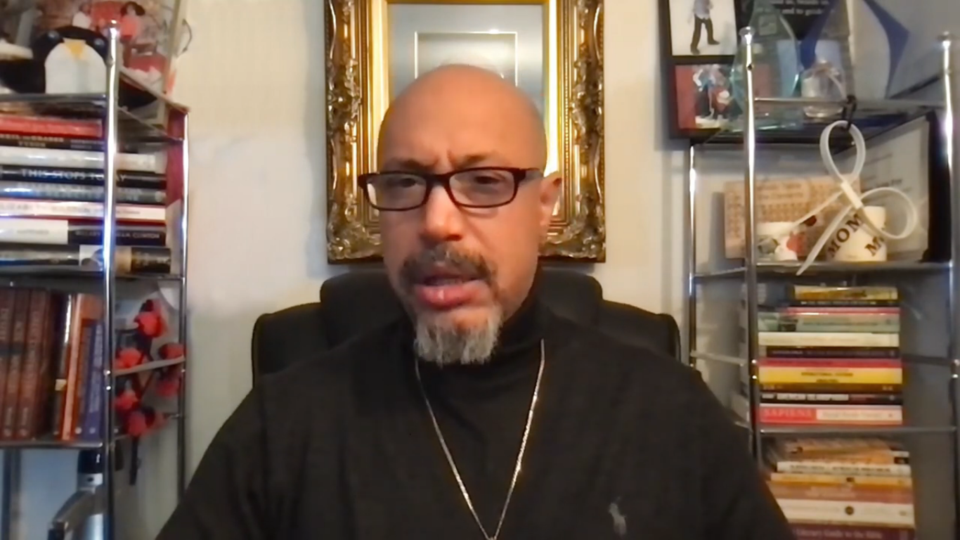

In an advertisement for advocacy group Consumers for Fair Legal Funding, the Rev. Kirsten John Foy — who’s serving as spokesman for the organization — shares his story of being victimized by a lawsuit lender while he waited for police to pay him a settlement.

The incident with police happened on Sept. 5, 2011 — NYPD officers arrested both Foy, at the time an aide to Bill de Blasio when he was the city's public advocate, and then-City Councilmember Jumaane Williams after that year’s West Indian Day Parade for alleged “trespassing” — though neither Foy nor Williams were ever ultimately charged with any crime.

“We proceeded to go through several police barriers and barricades with the permission of the initial officers,” Foy said, describing the 2011 incident to BK Reader, “only to run into a particularly obstinate and entrenched inspector who decided that it was offensive that we were present in that area, that we had isolated his secure space, and that he was going to unleash his officers on us and remove us violently if necessary, and proceeded to do so.”

That one moment would have drastic repercussions for Foy — during the arrest, he was left with a fractured kneecap and a torn rotator cuff, in need of surgeries and unable to work.

Foy sued the NYPD for monetary damages over the incident. Foy won the case after they admitted wrongdoing. But while the legal process dragged on, and with his wife also out of work caring for their then-newborn child, Foy and his family were in need of a source of income.

“With mounting medical bills and unanticipated expenses to come, we became economically strained,” Foy said.

That’s when an attorney on Foy’s case recommended he look into lawsuit lending. Also known as “pre-settlement funding” or “litigation funding,” lawsuit lending is the act of loaning funds to people expecting lawsuit settlements while their cases are still pending. The loans typically cover expenses before the settlement is received.

There were some red flags in the approval process for Foy’s lawsuit loan — for one, was told that in some cases, borrowers could end up paying back 100% of their settlement amount or more. But he said the lenders told him this was only something that happened in “extreme” cases — and given his financial predicament, Foy was not in a place to approach the loan with an overly critical eye.

“All you hear is, they’re prepared to give us the money now so you can take care of some of these mounting medical bills," said Foy, "so we can make sure that I’m mobile to get to the doctor with the baby because I’m not able to take you there, or we can pay some outstanding bills.”

Foy said he ultimately took out two loans to stay afloat. When he finally got his approximately $225,000 settlement from the NYPD, the lawsuit lender took well more than its fair share, he said — Foy and his family only ever saw about $75,000 of that settlement.

According to CFLF, Foy is far from the only person to fall victim to this sort of practice. The organization says victims of lawsuit lending abuse are often those with few other options — many don’t have any savings, credit cards or anyone to borrow money from.

“As a result, some of the most vulnerable New Yorkers – those who are lower-income, members of ethnic or racial minorities – are most likely to fall victim to this practice,” CFLF says. That’s why the organization — which describes itself as a coalition of social justice advocates, chambers of commerce, business groups and municipal leadership organizations — is dedicated to ending what it calls an “out of control” industry, and is pushing lawmakers to more heavily regulate it.

A decade after his experience, Foy said he’s grateful to be able to help spread the word about lawsuit lending.

“Eleven years later, I am now in a position to lend my voice as lifelong advocate for racial justice and economic justice and social justice, as a preacher and community leader, and as a husband and father to lend my voice to stopping and arresting the same savagery, economic savagery that took hold of my family (and stop it from) from taking hold of other families,” he said.