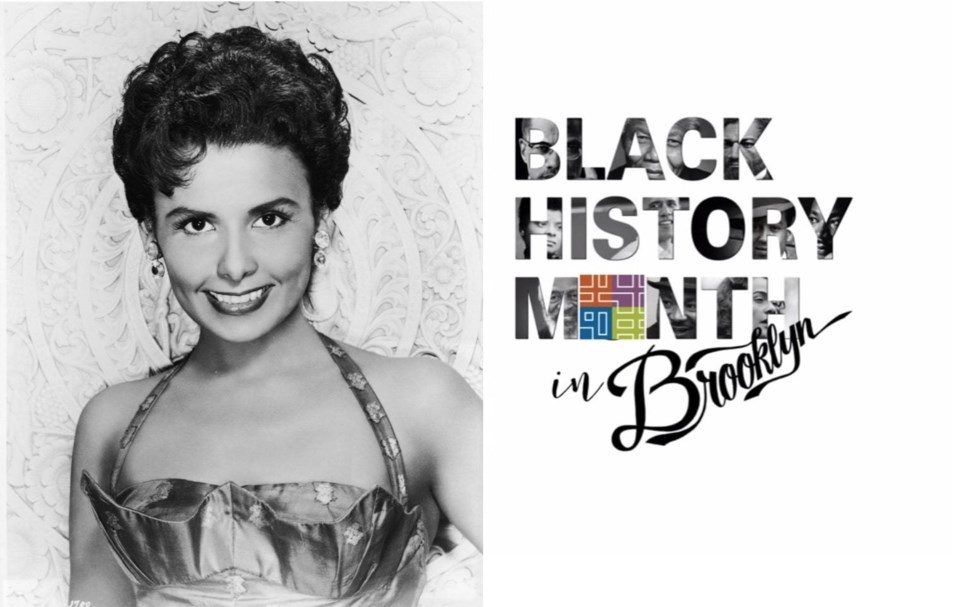

Singer and actress Lena Calhoun Horne was born in Bedford Stuyvesant on June 30, 1917.

All four of her grandparents were industrious members of Brooklyn’s Black middle class. Her paternal grandparents, Edwin and Cora Horne, were early members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and in October 1919, at the age of 2, Lena was the cover girl for the organization’s monthly bulletin.

At age 3, Horne’s parents separated and Lena was raised by her paternal grandparents until her mother took her back four years later at age 7. When Horne was 16, her mother pulled her out of school to audition for the dance chorus at the Cotton Club, the famous Harlem nightclub where the customers were white, the barely dressed dancers were light-skinned Blacks and the proprietors were gangsters.

A year after joining the Cotton Club chorus she made her Broadway debut, performing a voodoo dance in the short-lived show, “Dance With Your Gods,” in 1934.

At 19, Horne married the first man she had ever dated, 28-year-old Louis Jones, and became a conventional middle-class Pittsburgh wife. Her daughter Gail was born in 1937 and a son, Teddy, in 1940. The marriage ended soon afterward. Horne kept Gail, but Mr. Jones refused to give up Teddy, although he did allow the boy long visits with his mother.

She had been singing at the Manhattan nightclub Café Society when the impresario Felix Young chose her to star at the Trocadero, a nightclub he was planning to open in Hollywood in the fall of 1941.

In 1990, Horne reminisced: “My only friends were the group of New Yorkers who sort of stuck with their own group — like Vincente, Gene Kelly, Yip Harburg and Harold Arlen, and Richard Whorf — the sort of hip New Yorkers who allowed Paul Robeson and me in their houses."

Since Blacks were not allowed to live in Hollywood, “Felix Young, a white man, signed for the house as if he was going to rent it,” Horne said. “When the neighbors found out, Humphrey Bogart, who lived right across the street from me, raised hell with them for passing around a petition to get rid of me.” Bogart, she said, “sent word over to the house that if anybody bothered me, please let him know."

Roger Edens, the composer and musical arranger who had been Judy Garland’s chief protector at MGM, had heard the elegant Horne sing at Café Society and also went to hear her at the Little Troc. (The war had scaled down Mr. Young’s ambitions to a small club with a gambling den on the second floor). He insisted that Arthur Freed, the producer of MGM’s lavish musicals, listen to Horne sing.

Then Freed insisted that Louis B. Mayer, who ran the studio, hear her, too. He did, and soon she had signed a seven-year contract with MGM. She was not the first Black performer under contract to a major studio — MGM had signed the actress Nina Mae McKinney for five years in 1929 — but she was the first to make an impact.

Horne’s first MGM movie was “Panama Hattie” (1942), in which she sang Cole Porter’s “Just One of Those Things.” Writing about that film years later, Pauline Kael called it “a sad disappointment, though Lena Horne is ravishing, and when she sings you can forget the rest of the picture." Horne was stuffed into one “all-star” film musical after another — “Thousands Cheer” (1943), “Broadway Rhythm” (1944), “Two Girls and a Sailor” (1944), “Ziegfeld Follies” (1946), “Words and Music” (1948) — to sing a song or two that, she later recalled, could easily be snipped from the movie when it played in the South, where the idea of an African-American performer in anything but a subservient role in a movie with an otherwise all-white cast was unthinkable.

“The only time I ever said a word to another actor who was white was Kathryn Grayson in a little segment of ‘Show Boat’ ” included in “Till the Clouds Roll By” (1946), a movie about the life of Jerome Kern," Horne said in an interview in 1990. In that sequence she played Julie, a mulatto forced to flee the showboat because she has married a white man.

But when MGM made “Show Boat” into a movie for the second time, in 1951, the role of Julie was given to a white actress, Ava Gardner, whose singing voice was dubbed. (Horne was no longer under contract to MGM at the time, and according to James Gavin’s Horne biography, “Stormy Weather,” published last year, she was never seriously considered for the part.)

And when Horne herself married a white man — the prominent arranger, conductor and pianist Lennie Hayton, who was for many years both her musical director and MGM’s — the marriage, in 1947, took place in France and was kept secret for three years.

In 1945 the critic and screenwriter Frank S. Nugent wrote in Liberty magazine that Horne was “the nation’s top Negro entertainer.” In addition to her MGM salary of $1,000 a week, she was earning $1,500 for every radio appearance and $6,500 a week when she played nightclubs.

She was also popular with servicemen, white and black, during World War II, appearing more than a dozen times on the Army radio program “Command Performance.

“The whole thing that made me a star was the war,” Horne said in a 1990 interview. “Of course the Black guys couldn’t put Betty Grable’s picture in their footlockers. But they could put mine."

Touring Army camps for the U.S.O., Horne was outspoken in her criticism of the way Black soldiers were treated.

“So the U.S.O. got mad,” she recalled. “And they said, ‘You’re not going to be allowed to go anyplace anymore under our auspices.’ So from then on, I was labeled a bad little Red girl.”

Horne later claimed that for this and other reasons, including her friendship with leftists like Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois, she was blacklisted and “unable to do films or television for the next seven years” after her tenure with MGM ended in 1950.

Although absent from the screen, Horne found success in nightclubs and on records. “Lena Horne at the Waldorf-Astoria,” recorded during a well-received eight-week run in 1957, reached the Top 10 and became the best-selling album by a female singer in RCA Victor’s history.

In the early 1960s Horne, always outspoken on the subject of civil rights, became increasingly active, participating in numerous marches and protests. In 1969, she returned briefly to films, playing the love interest of a white actor, Richard Widmark, in “Death of a Gunfighter.” She was to act in only one other movie: In 1978 she played Glinda the Good Witch in “The Wiz,” the film version of the all-Black Broadway musical based on “The Wizard of Oz.” But she never stopped singing.

Lena Horne died on May 9, 2010, in Manhattan. She was 92. She is survived by her daughter Gail Lumet Buckley, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Looking back at the age of 80, Horne said: “My identity is very clear to me now. I am a Black woman. I’m free. I no longer have to be a ‘credit.’ I don’t have to be a symbol to anybody; I don’t have to be a first to anybody. I don’t have to be an imitation of a white woman that Hollywood sort of hoped I’d become. I’m me, and I’m like nobody else.

Lena Horne, we acknowledge your groundbreaking accomplishments in TV, film and music and we honor your invaluable contributions to the civil rights of all.

*Sources, The New York Times 5/10/10 By ALJEAN HARMETZ, patch.com