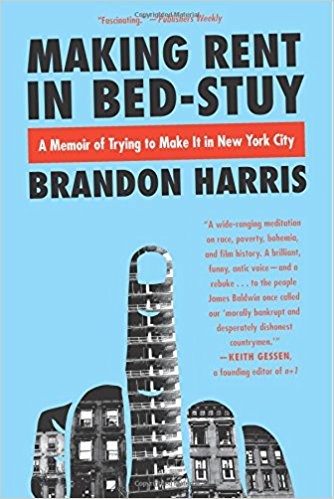

Cultural activities are flourishing in Bedford-Stuyvesant. In the summer of 2016 Fulton Park got a theater, and then the Billie Holiday Theater officially reopened in May after a two-year renovation. On Thursday, the Brooklyn-based literary magazine n+1 hosted a discussion session on filmmaker/film critic Brandon Harris's critically acclaimed book Making Rent in Bed-Stuy: A Memoir of Trying to Make It in New York City, followed by a Q & A with the author.

Making Rent in Bed-Stuy is a witty account on the challenges, and at times even physical danger, Harris faced when he was trying to fulfill his cinematic ambitions in New York City, starting with an attempted robbery in front of his then home at Taaffe Place in Bed-Stuy. In self-defense, Harris had struck the robber who sauntered off, cursing and shouting, " this is Bed-Stuy, bitch!"

"This is Bed-Stuy!" This exclamation seemed to be more than a geographical reference. One may assume the robber had taken violence as a way of faring in Bed-Stuy. But ranked by NYU Furman Center for Urban Policy as the 7th most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods in the city, such a scene may soon be history.

Gentrification and its subtle complications loomed large during the discussion. Once a film school graduate who was able to rent an apartment for $2,400 per month with his friends, now a filmmaker and a regular contributor of The New Republic and The New Yorker, Brandon Harris identified himself as a gentrifier and was struck by the gulf between the gentrifiers and the gentrified, namely the poor.

Yet gentrification is a much more complex process than landlords pricing out destitute tenants. According to Harris' observation, Bed-Stuy now is going through the more "mature", later-stage of gentrification. It means relatively well-to-do people like Harris himself are at risk of being pushed out by the wealthier and more resourceful. If this is the current trend in Bed-Stuy, is it too big a leap to ask: will some streets in Bed-Stuy become the examples of high-rent blight, the kind of blight where rents become so high as to be untenable, yet landlords hold out which leaves buildings sit vacant for years?

Stories Harris shared also revealed that gentrification did not just happen in apartment buildings or in housing courts, but extended to the improvement of community amenities such as parks and cultural spaces which usually pushed out homeless people. "The neighborhood was completely transformed," said Harris. The homeless men he once saw in various Bed-Stuy parks when he was shooting films a few years ago are not there anymore; they were pushed out for the sake of building a better community.

The discussion inspired thoughts on the complexity lying underneath the sweeping phenomenon of gentrification and its possible impact on the people who often are not considered to be subject to it. The book is a good read for anyone who is interested in the thorny yet fascinating landscape of Bed-Stuy and the many iconoclastic cultural figures it nurtures. But Harris also gives a personal examination of a new generation of African-American identity and its self-exploration.