Journalism—and more specifically hyper-local journalism including student newspapers—has never been more important to the preservation of our democracy and ensuring a voice for the voiceless.

On the second Thursday of nearly every month, three or four of us vintage New Yorkers, ranging in age from 92 to 94, meet to vigorously discuss politics, the media, the culture scene and to recall the years they spent together more than seven decades ago on the staff of the Brooklyn College student newspaper, Vanguard.

The newspaper was kicked off campus in 1950 by an authoritarian college administration, which was rattled by its pugnacious coverage of campus affairs. But now it has returned and thereby hangs a tale of New York grit and stands as an important part of Brooklyn College’s culture.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the group—including this writer—met in person at a Turkish restaurant on the Upper West Side. Now we gather on Zoom. Our minds are alert, and we all have strong opinions about the day's issues, including the presidential campaign and threats to freedom of the press.

The former Vanguard colleagues are joined each month by a junior honorary member (age 79) whose husband, a formative member of the luncheon group, died two years ago. Two of the survivors— Connie Serouya Goldfarb and this writer —recently lost their spouses of more than 69 years, both of them also Brooklyn College graduates.

The Vanguard ties were strained, but not broken, in 1950 when a thin-skinned college president named Harry Gideonese, long-offended by Vanguard's muckraking ways, orchestrated its ouster as the student newspaper. When the staffers and some supporters on campus chipped in and put out a paper of their own, the school's administration suspended several of the top editors and put dozens of staff members on probation.

The widowed European-born mother of one staffer received a letter from the Dean of Students stating that her son had been put on "probation," but being an upstanding lady of the old school, she questioned her son about the meaning of the word "probation."

"It's an honor, Mom," he assured her, only half-lying, and then he contributed his spare cash into helping put out two insurgent papers, along with many other Vanguard staffers and campus supporters.

The off-campus ventures, first named Draugnav (Vanguard spelled backward) and then Campus News, struggled for several weeks before giving up the fight after running out of funds. That enabled the student journalists to finally concentrate on their studies and future careers.

Many of those careers have been illustrious. The late William Taylor, the last editor of Vanguard, went to Yale Law School, joined the NAACP Legal Defense Fund under Thurgood Marshall, and was appointed general counsel of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission by President Kennedy and then as staff director by President Johnson.

Mitchel Levitas, who died three years ago, held several top editorial posts at The New York Times. He and his wife Gloria met through the Vanguard. Albert Lasher was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal and an editor at Business Week magazine. His widow, Stephanie Fuchs Lasher, is the honorary member of the group. They met when she was press secretary to Mayor John Lindsay's wife Mary and Albert's Columbia J-School classmate Woody Klein was the mayor's spokesman. The late Rhoda Hendrick Karpatkin became the general counsel and then the president of the Consumers Union. She met her husband Marvin Karpatkin at Vanguard and they both later went to Yale Law School.

Among those still taking part, Connie Goldfarb and Gloria Levitas became college professors. Henry Grinberg (and his wife Suzanne, another junior honorary member) long practiced as a psychoanalyst and writes novels. Trudi Novina Coakley became a reporter for the New York World-Telegram & Sun and then a public relations executive. Giselle Cohen Stevens, the last managing editor of Vanguard, had a distinguished business career.

Others, nearly all of them immigrants or children of immigrants and the first in their families to go to college, flourished in journalism, academia, business, the law and other pursuits. They all say the Vanguard experience and its struggle against unjust authority helped shape their lives to this day. Over the years, they frequently ended their communications with the motto: "Vanguard Lives!"

Their bond is so strong that 20 years ago, they and other surviving “Vanguardites” endowed a $1,000 annual prize for outstanding student journalism. Many of the winners of that prize have gone on to notable careers in news and public service.

No longer pariahs to the college administration that once censured them, the former Vanguardites are now honored for their advocacy of a free campus press.

In 2006, then-president Christoph Kimmich installed a commemorative brass plaque on the door of the old Vanguard office just a few paces down from his own, and a year later he awarded an honorary doctorate to William Taylor for his continuing work as a civil rights leader, especially in the field of education. In 2000, Kimmich's successor, Karen Gould, spoke about the value of a vigorous press at a dinner on campus attended by 35 former staff members and spouses marking the 50th anniversary of the paper's ouster.

In 2019, current Brooklyn College President Michelle J. Anderson, who succeeded Gould as president, arranged an exhibit of Vanguard's history in two big display cases outside her office and invited us luncheoneers to a reception in her board room to celebrate the history and legacy of Vanguard. She thanked the group "for using your free speech rights to hold power to account."

"That is the role of a journalist in a free society, and you managed to fulfill that noble role as young college students," she added.

Also attending the reception was Quiara Vasquez, the then editor-in-chief of The Kingsman, the student newspaper that succeeded the ousted Vanguard. The Kingsman and Excelsior, its rival campus paper, both had been having trouble in recent years recruiting staff members and they decided to merge. But what to name the combined paper that will carry on this important campus legacy?

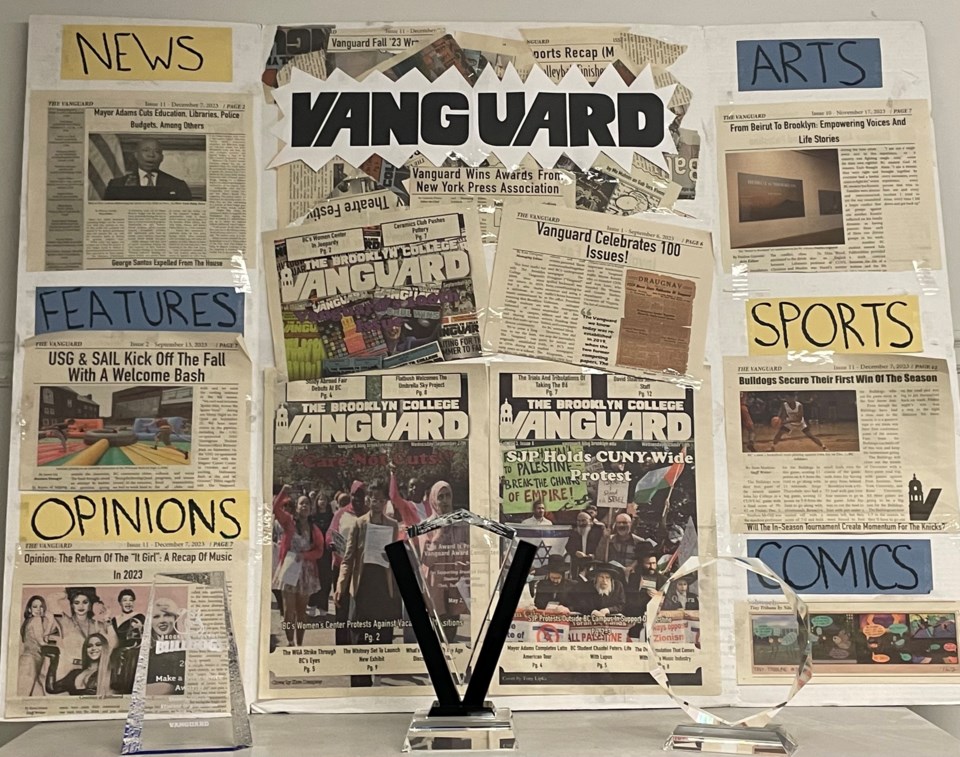

Vasquez, impressed by the Vanguard’s history on display and the discussion of its legacy at that reception, proposed a return to the old name. It was quickly adopted, and the paper is now flourishing with a modern design and the new/old name.

The surviving old-timers now proudly relish the fact that indeed "Vanguard Lives!”

Myron Kandel graduated from Brooklyn College in 1952. He was the financial editor of the Washington Star, the New York Herald Tribune and the New York Post and served for 25 years as the founding financial editor of CNN. He was also a staff member for one of Brooklyn College’s first student newspapers, Vanguard, and today serves as an honorary Governor on the Brooklyn College Foundation Board.