By Sonja Anderson

At age six, Mary Gethins saw her mother dragged down a flight of subway steps by a mugger. They were on their way home, leaving the 182nd Street D train station in Fordham Heights, the Bronx. When Gethins’ mom didn’t let go of her purse, the thief took her, screaming, with it. Cash, keys, ID and her last paycheck from her job at Woolworth’s: gone.

“I can still hear her screaming,” Gethins says. “You can't—you can't go and take something that doesn't belong to you…Even if you’re not assaulting them and you're just taking your property, you leave something behind that scars people forever.”

Years later, it happened a second time. When Gethins’ mother came home from the supermarket bottle collection machine one day and told her 18-year-old daughter she’d been robbed, Gethins asked which path she’d taken home.

Then Gethins picked up a butcher knife and walked out the door.

“I walked the same route she did to see if I could find that person,” Gethins says. “Lucky for him, I never did.”

For the past 25 years, these memories have influenced Gethins’s work as a member of the Guardian Angels, the volunteer crime-watch organization founded in 1979 by Curtis Sliwa. And since 2016, she’s led a special group within the Angels, the Perv Busters. They aim to protect New Yorkers, especially women on the subway, from sexual offenders. Gethins was motivated by yet another experience from her youth to lead the group: she was sexually assaulted as a young girl.

“Nobody has the right to touch anybody,” says Gethins, 51. “Nobody has the right to force themselves on you. You could be the smartest person in the world, and you could find yourself in the most terrifying situation. And you would hope that somebody would be there to help you.”

In 2016, Gethins says, Sliwa noticed an influx of emails from citizens concerned about sex crimes in public. He chose Gethins to lead a new group focused on helping to prevent assaults and catch perpetrators.

“It made sense because he already knew my life story,” Gethins says. She had told Sliwa about what happened to her as a kid. “Being an established patrol leader, he always had me in mind.”

Gethins joined the Angels in 1998. They had gained notoriety through the 1980s and ‘90s, when crime in New York City reached epidemic proportions.

Now, the Angels have 5,000 members spread over 130 chapters in 13 countries, according to Senior Director Arnaldo Salinas, who says membership in New York City is about 350. The Angels’ mission is to “protect their communities,” and they do that through neighborhood “patrols.” They walk streets and subways, looking out for crime and occasionally making a citizen's arrest.

“Some people are a little bit too comfortable, expecting crime is not really going to happen here or there,” says Gethins. “Believe it or not, it’s popping up everywhere. You just have to be vigilant and try to control that by reporting crime or getting a little bit more involved.”

The Perv Busters say they operate on tips. New Yorkers will send them descriptions and photos of incidents, Gethins says, like a man exposing himself on the subway or taking photos up a rider’s skirt. They’ve also received tips from law enforcement, government and transit workers, says Salinas. He says the Angels verify that an incident is actually happening by sending a couple of their members to the scene to observe the act.

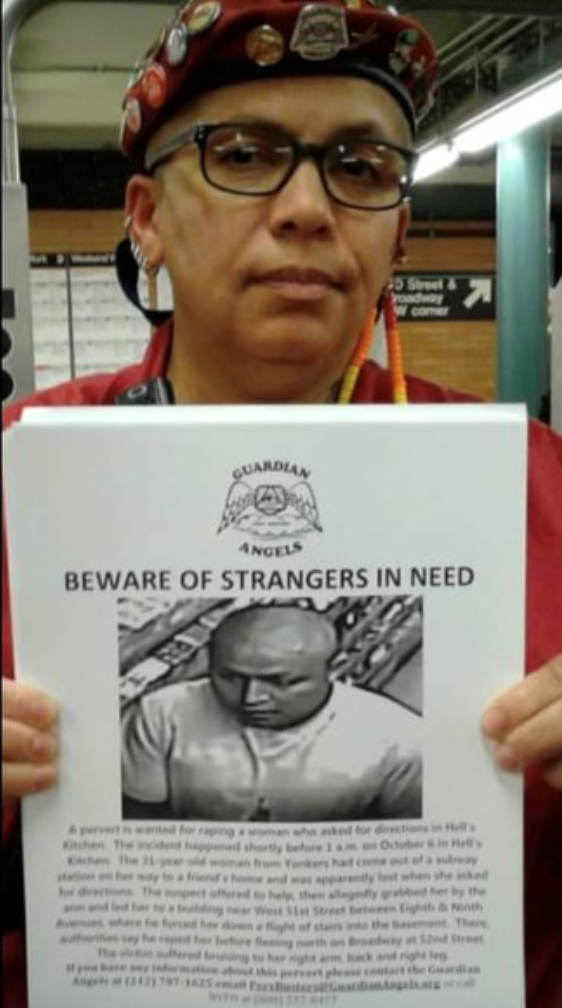

Gethins says any tip that gets “the Curtis stamp of approval” is forwarded to the police. Then the Perv Busters draw up an 8½- by 10-inch, wanted-style poster that includes a description of the crime and sometimes an image of the accused, their own contact information and the NYPD’s tip line. The most recent flyer detailed repeated verbal assault of a jogger in Carl Schurz Park on the Upper East Side.

Once a flyer is ready, Gethins dons a red jacket, black pants and a red beret adorned with pins—rainbows and pride-themed messages, shamrocks and Golden Girls—and gathers a group of Angels. They roam parks and train platforms, posting up two-by-two or in single file, hanging flyers near where incidents have been reported and making their presence visible.

“And we'll talk to people as we give them out,” Gethins says of the flyers. “We tell them, ‘This occurred at such and such time on this line or at that station—just be aware of your surroundings.’”

Salinas says Perv Buster teams are purposefully composed of mostly women, who make up about 45 percent of the organization.

“Who better to speak out and say, ‘No, no, my brother, not today,’ other than women?” Salinas says. “The impact comes from women being strong, and standing up, and saying, ‘No, you are not gonna do this to us.’”

On a brisk, spring Thursday evening, Gethins meets a fellow Perv Buster outside Ray’s Candy Store in Alphabet City. They pat each other down, as all Angels must do before going out, to make sure they have nothing that could cause trouble or be used by an attacker to harm them—no pocket knives, no pepper spray. The Perv Busters are just two-strong tonight: Gethins and rookie Juli Oliver, a 46-year-old professional home organizer from Hell’s Kitchen.

A few others bailed or couldn’t commit, which peeves Gethins, even though there are no flyers to post today. Oliver always expects to see Gethins on the street.

“She’s always patrolling,” she says. “Always. Always.”

Oliver knows Gethins by her Guardian Angels nickname, “KC,” which she chose when she joined because of an affinity for disco group KC and the Sunshine Band. Her first impression of KC?

“Badass,” Oliver says with reverence. “Knows her stuff.”

Gethins, 5’5”, walks with an upright bearing. She makes eye contact while talking to you, but keeps her focus on the periphery, to be aware of her surroundings. She’s worked in security most of her professional life, now for Columbia University. A born and bred Bronxite, Gethins observed the Angels in her borough as a kid.

“I used to see them when I would be on the trains, going wherever with my mom,” says Gethins. “And, you know, it's very memorable to see the Guardian Angels. Everybody was dressed in red with these funny-looking hats, and I watched what they were doing.”

Gethins wanted to join the Angels at 16, but her mother gave an unequivocal “No.” Gethins wanted to fight back against the bad guys, like the men who mugged her mom.

Gethins’ mom wanted to keep her daughter out of any more danger. A few years before, she’d been preyed on by a pedophile.

As kids, Gethins and her friends frequented the Paradise Theater on the Grand Concourse, and a “neighborhood, Mr. Fix-It” type of guy would often drive them to and from. One day, 12-year-old Gethins was the last kid in the car to be dropped off. He raped and impregnated her.

She spent a month in the hospital after giving birth to her son, both of them jaundiced and she anemic.

She doesn’t know what became of the rapist. Gethins later learned she wasn’t his only victim, she says, and her mother told her he’d been arrested. She remembers child welfare officials attempting to make her give up her son.

“They tried to label me as a child of the street,” Gethins says. “I wasn't allowed to leave the front stoop until I turned 12, and, you know, this just happened to me. And they said, ‘Oh, no girl gets pregnant on the first try.’ They were really vulgar and nasty.”

Gethins stays vigilant in and out of uniform, sometimes confronting older men she sees ogling girls and young women. Gethins has never witnessed an assault while walking with the Guardian Angels. If she were to see an attack unfolding, though, she doesn’t plan to be a bystander.

“If it looks like I can jump in and I wouldn't wind up getting hurt, I would go for it,” she says.

Gethins left the Bronx for Brooklyn in 2019. She lives in the Angels’ Canarsie headquarters—a house once owned by Sliwa’s parents’—with another member, a dog and nine cats. Her son, now 38, lives in Spanish Harlem, and she has a 35-year-old daughter in New Jersey.

Walking Alphabet City, Gethins's and Oliver’s bright red jackets and berets pop against the darkening sky. They’re conspicuous, and it’s deliberate. Some Angels, like Oliver, bristle at the notion that their work is symbolic, that they’re mainly a visually striking presence that lets people know someone’s watching.

Yet Gethins learned the power of that presence during her first days as an Angel, when she noticed she didn’t see any crime happening while out with groups.

“That's when I figured out once we’re in uniform, it's a natural deterrent,” says Gethins, recalling times she believes drug deals broke up because of approaching Angels. “I've seen people over the years stop in the middle of what they're doing and then go in opposite directions. So, that's something…It's a big deal that we're a deterrent.”

Public opinion of the Guardian Angels trended high for a while after their outset. Studies showed that while they had little or no effect on crime rates, they did improve perceptions of public safety. Nowadays, the group polarizes. Sliwa, who ran as the Republican candidate for mayor in 2020, lost the election by nearly 40 points, after a campaign that saw the Angels again labeled vigilantes.

In training, Gethins says, they learn to ignore “verbal abuse.” The most common heckle goes something like, “Go home—we don't need you.”

Gethins and Oliver get no negative comments as they walk Alphabet City. A few pedestrians stop to thank them. One man earnestly asks Gethins to “tell Curtis I said hello.” Another approaches in Tompkins Square Park to say, “I'm glad you guys are still walking on the streets, man. We need you.”

When she does get heckled, Gethins considers when to respond, because she never knows who might be armed. Walking the streets can be risky, Gethins says, but her belief in the Angels’ mission always brings her out again.

“When you put on the uniform, it kind of gives you this nice complex, like the feeling you get when you see Superman step out of the phone booth,” says Gethins. “It's a big motivator, and I still get that to this day. I could be tired as hell, but I will still get that same feeling because I'm getting ready to help.”

Sonja Anderson is a Brooklyn-based writer and reporter. She's currently studying at CUNY's Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism.