By Jonathan Soffer, who is a professor of history at NYU Tandon School of Engineering and the author of “Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York.”

For decades, Brownsville, Brooklyn, has suffered from some of New York City’s highest crime rates, while Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, has remained relatively low-crime. To understand why, it is important to examine not only criminal justice policies but the history of investment, development and service delivery in the two neighborhoods.

Brownsville’s problems go back to its founding. In the 1860s and 1870s, its developers built heavily polluting “light” industry and cheap tenements to house sweatshops and the workers who toiled in those factories. It was known as a high-crime area as early as the 1930s and 1940s, when it was notoriously a base for the crime organization Murder, Inc. After World War II, when people of color migrated into the neighborhood in large numbers, public housing projects began to replace those early tenements.

Because so much of its housing stock is public, Brownsville has been largely impervious to gentrification. But the high crime rates and comparative lack of green space, street trees and shade have also kept it poor and hot.

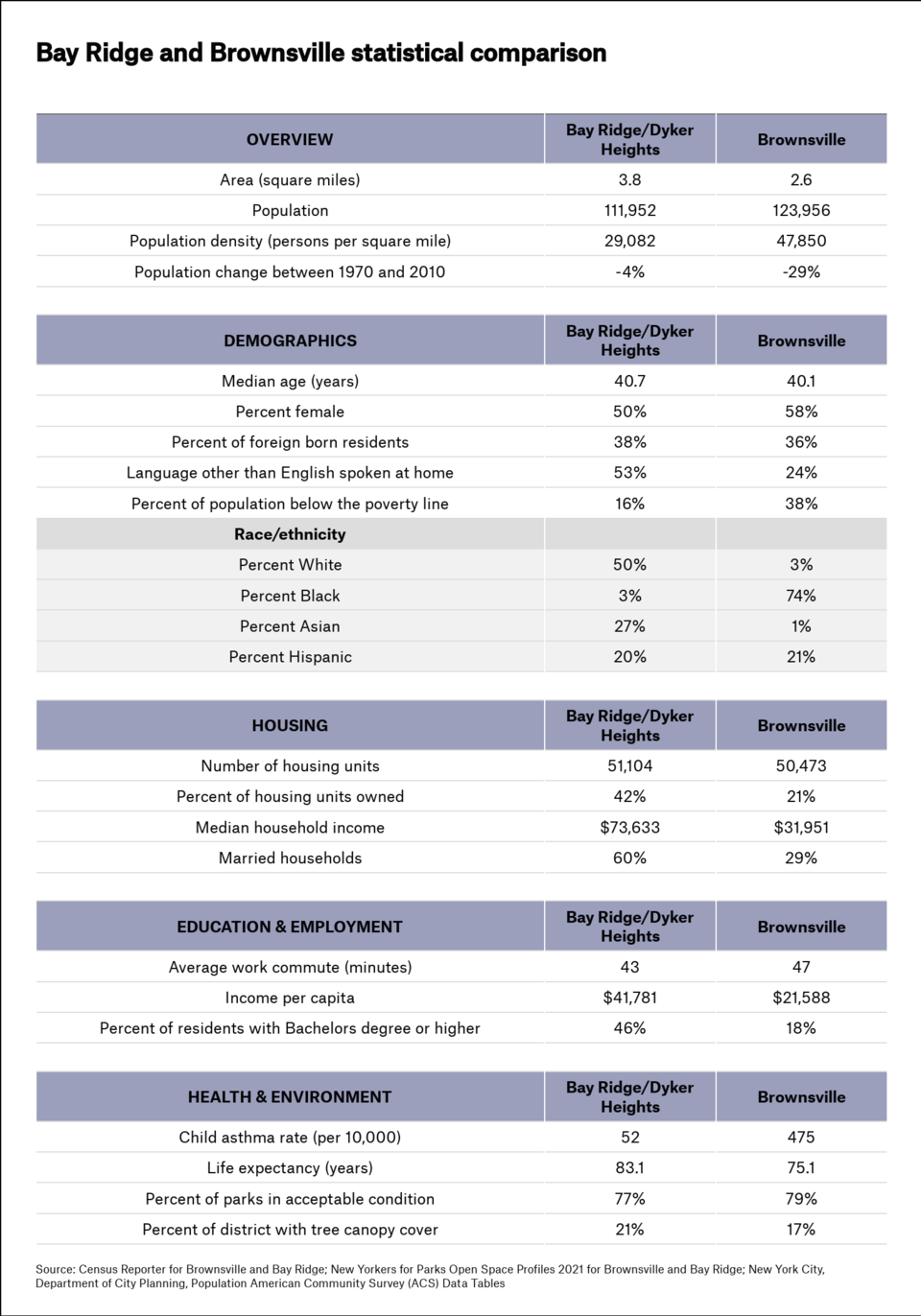

Bay Ridge has 20% more tree cover than Brownsville.

Bay Ridge, in contrast, with its views of the Verrazzano Narrows and cool breezes blowing off the water, is more environmentally friendly to human habitation. Bay Ridge has 20% more tree cover than Brownsville. Initially built as a retreat for the rich, the neighborhood has attractive mansions on its bluffs, just a short boat ride from Manhattan. It gained significant federal investment in the form of a U.S. Army base at Fort Hamilton and the massive Brooklyn Army Terminal, recently redeveloped for start-ups and retail, art and tech businesses.

Although the neighborhood has become much more diverse, white racism has certainly been present over the generations. Many of the streets on the military base were until this year named for Confederate officers such as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, emphasizing the area’s hostility to African Americans.

Most of Bay Ridge’s mansions were replaced by apartment buildings when the BMT subway reached the neighborhood in 1915. On the Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps of 1938 — maps that guided investment in housing for generations — Bay Ridge was the only green-colored “A”-rated neighborhood in Brooklyn, eligible for loans and new construction because of its white population. (In contrast, Brownsville was disinvested after 1938, when it was redlined with a “D” rating, due to, among other factors, “Communistic type of people,” “poor upkeep” and “mixture of races.”) Bay Ridge became a haven for Irish and Norwegian immigrants. Today Bay Ridge sees more varied immigration; the largest new group is Chinese, with significant numbers of Italians, Russians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Greeks, Koreans and Arabs.

The HOLC maps directly affected private investment in housing in the two neighborhoods. Could differences in housing and public space in these two precincts explain the difference in crime rates? This question is significant to citizens and researchers looking to reduce crime by design instead of coming to terms with economic inequality.

A one-time intervention, such as a building design, cannot by itself transform social relations.

Architect and city planner Oscar Newman’s book “Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design,” one of the most ambitious attempts to combat crime with design, compares two Brownsville projects of the New York City Housing Authority: the low-density Brownsville Houses and the high-rise Van Dyke Houses. Newman claimed that the high-rise apartment towers were inherently more dangerous and fostered crime and disorder — but that conclusion has been challenged by subsequent generations of scholars. Fritz Umbach and Alexander Gerould observe:

The high-rise Van Dyke Houses were not simply higher, they also sheltered significantly larger families. ... The regression tables tucked away in Defensible Space’s final pages quietly contradict the book’s conclusions by demonstrating that crime in the complexes was more closely correlated with family size (a rough proxy for child-to-adult ratios) than building height.

Newman’s study and the critiques that followed highlight the jeopardy in making facile comparisons between building designs, rather than studying the people who live in them, their affluence or poverty, or the level of city services and investment. Moreover, a one-time intervention, such as a building design, cannot by itself transform social relations.

The structures of capital and racial hierarchy proved far more decisive than physical structures. The historian Craig Steven Wilder demonstrates that as racial minorities moved into Central Brooklyn, real estate interests restricted homeowners’ access to capital for the improvement and maintenance of their older brownstone homes. At the same time, the city began to reduce services, such as sanitation. Developers aimed to make money, deliberately steering white migration into more profitable new construction in segregated neighborhoods, including Bay Ridge and Bensonhurst, and the suburbs.

A comparison of statistics between Brownsville and Bay Ridge shows dramatic differences in earnings, wealth, health (especially asthma rates), life expectancy, green space and access to capital, which, along with race, likely determined patterns of investment in the two neighborhoods.

Another stunning divergence between the two neighborhoods was the rate of decrease in their populations between 1970 and 2010. Bay Ridge suffered a relatively small 4% decline in that period, mostly as a result of displacement and demolition of housing for the construction of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. In the same period, Brownsville’s population declined 29%, even as the denser NYCHA towers replaced the original landscape, which was more varied in structure and use. The Brownsville population decline is even more dramatic when taking into account the neighborhood’s previous decades of population decline. By 1970, Brownsville had already lost 30% of its 1940 population peak, and by 1980 the population was down to half of its 1940 peak.

The first stage of population decline probably came because of departures from Brownsville by more economically successful whites (a largely working-class Jewish population), bolstered by their access to federally subsidized credit for housing in other neighborhoods, and by the benefits of the GI Bill — benefits that did not flow equally to African Americans. Many residents of Jewish Brownsville considered it a place to work their way out of.

A strong program of public housing began with the construction of Brownsville Houses in 1948, and at the beginning, it was a very successful, racially integrated development. Up to the mid-1970s, however, the thousands of NYCHA-built housing units were the only new housing in the area. Federal policies allocated those units to poorer and poorer tenants, which also effectively segregated the neighborhood.

The Kumbaya Highway

Despite their pronounced differences, Bay Ridge and Brownsville are curiously connected through the Bay Ridge Branch of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR), which forms Brownsville’s eastern boundary. It is a freight-only line that has not carried passengers for nearly a century.

A rare right-of-way through the middle of Brooklyn and Queens, the Bay Ridge Branch has sparked activists’ and planners’ dreams of a better Central Brooklyn since the 1940s, when the Brownsville Neighborhood Council, responding to the electrocution of five children on the line over the course of 1946, first proposed covering the rail line with a park to provide safety and more recreational space.

In the 1950s, as kids continued to die on the third rail, the ministers of Brownsville’s growing Black congregations mobilized to demand better fencing around the line. That the request had to be repeated suggests the inability of Brownsville’s poor and working-class residents to get so much as a fence, even when the neighborhood was still predominantly white. So the Bay Ridge Branch itself is emblematic of the city’s neglect of Brownsville’s children.

As Brownsville became more and more of a Black and Hispanic neighborhood in the 1960s, with one of the largest concentrations of public housing in New York City, the Lindsay administration embraced a plan to break the “ghetto” walls formed by the Bay Ridge Branch with an ambitious plan for both a “Linear City” and the Central Brooklyn Expressway laid on top of the rail line.

Lindsay and the Linear City designers hoped that the highway would provide a bridge between Brownsville and neighboring white communities, with integrated schools and other institutions — a plan so idealistic that the historian Thomas Campanella scathingly described it as a “kumbaya highway.”

While Bay Ridge continued to receive private investment and relatively good city services, in part because of its high HOLC ratings, the story of Brownsville is a more complex one of declining public investment.

As the 1960s progressed, the Lindsay and Beame administrations first raised, then dashed the hopes of Brownsville residents for an integrated neighborhood with good schools and clean streets, ultimately mangling the area with an urban renewal program that was both badly planned and insufficiently executed. The program demolished much of the old low-rise housing in the neighborhood and never got around to rehabilitating what was left. Between 1964 and 1970, even white Brownsvillians who had been dedicated to integration left the neighborhood.

In 1968, the city switched control of schools from the central administration to local boards. This created a racially polarizing controversy when the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school fired several white teachers, triggering a strike by the United Federation of Teachers. In the wake of that strike, many white politicians allied with the teachers union and may have retaliated against the community by reducing city services and investment. For example, in 1970, trash pickup was reduced from six times a week to two. In the “Brownsville Trash Riots” of 1970, demonstrators collected a mountain of trash and burned it in the middle of the street, which kicked off two nights of unrest. In response, the Lindsay administration briefly improved trash collection, but those gains faded with the drastic cuts of the fiscal crisis five years later. Over the following decade, much of what was left of the existing low-rise housing stock was left to burning, scavenging, looting and abandonment.

While Bay Ridge continued to receive private investment and relatively good city services, in part because of its high HOLC ratings, the story of Brownsville is a more complex one of declining public investment. Between the city’s fiscal crisis and the Nixon administration’s cutbacks in federal housing programs, Brownsville was cut off from its main sources of public investment in the 1970s, while for private investment, it remained where it was placed by the HOLC mappers: at the bottom of the list.

In contrast to the fate of low-rise housing, NYCHA was a bright spot for Brownsville in the 1970s, as it successfully revitalized Van Dyke Houses — which, according to housing historian Nicholas Dagen Bloom, “very well could have become uninhabitable in the same manner as Pruitt-Igoe,” the infamous complex of 33 buildings in Saint Louis, designed by World Trade Center architect Minoru Yamasaki, that was demolished between 1972 and 1975. By 1975 at Van Dyke, Bloom observes, “morale was up and the grounds cleaner.”

The biggest improvements in Brownsville in the following decade occurred because they were proposed first by the local community and later supported by the Koch administration. Organized by the religiously based East Brooklyn Congregations, the Nehemiah housing plan of the early 1980s built thousands of two- and three-bedroom row homes that were affordable, at least for the “upper stratum” of the Brownsville community. Many families who came from the projects were able to buy homes with incomes as low as $25,000. Even so, the Nehemiah plan homes, which require mortgage qualification and a down payment, are still too expensive for many of Brownsville’s residents.

The latest attempt to improve the neighborhood, the Brownsville Plan, aims to be “a community-driven process to identify neighborhood goals, form strategies to address local needs, and find resources to fill gaps in service.” With the election of born-in-Brownsville Eric Adams as mayor of New York, the plan is likely to have strong support from City Hall and perhaps a better chance of moving forward. The plan aims to add 2,500 affordable new homes and coordinate private and public investment to upgrade parks, recreation centers and other facilities.

Conclusion

There is no simple way to correlate the respective high and low crime rates of Brownsville and Bay Ridge to their differences in income and wealth or to the quality of their respective environments, aspects that deserve further investigation. Bay Ridge’s white and subsequently Asian immigrant population had more wealth and opportunities, as well as a greater assemblage of public goods and investment — a legacy of the area’s white middle-class advantages — which in turn enabled them to produce a neighborhood space with more amenities. In contrast, Brownsville’s poor residents of all ethnicities climbed a steep hill of disadvantage. These differences probably led to Brownsville’s persistence as one of the city’s highest-crime neighborhoods, and Bay Ridge’s as one of the lowest.

This article was first published in Vital City, a new venture focused on advancing practical solutions to public safety problems in New York City.