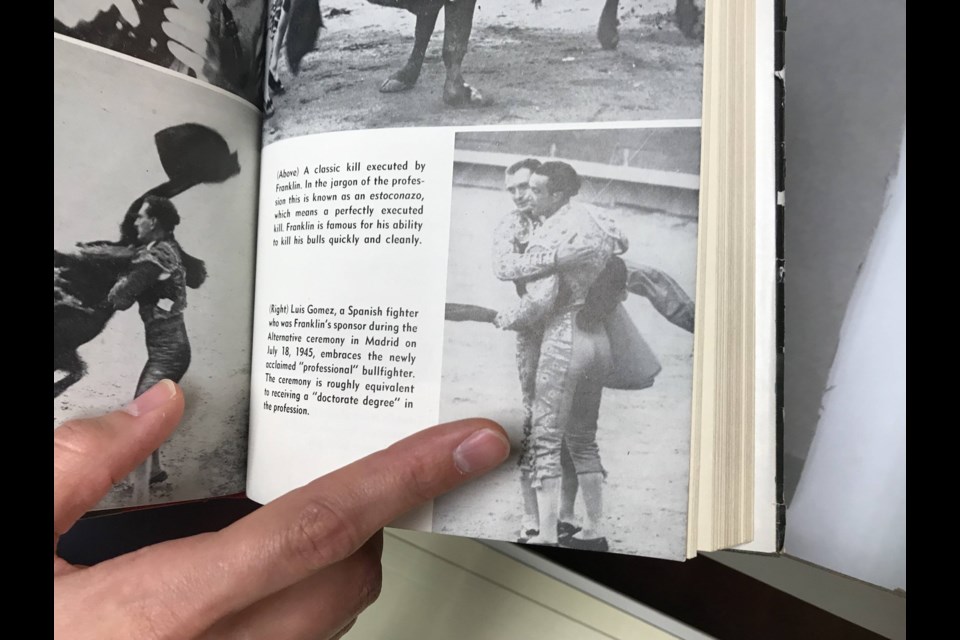

An old photograph captures the day Sidney Franklin, a gay, Jewish man from Park Slope, became a full-fledged bullfighter in 1945.

Franklin rose to notoriety and fame as the first and only Jewish-American matador to fight in the arenas of Mexico and Spain.

His life story is the inaugural subject for Out of the Box, a lecture series at the Center for Jewish History.

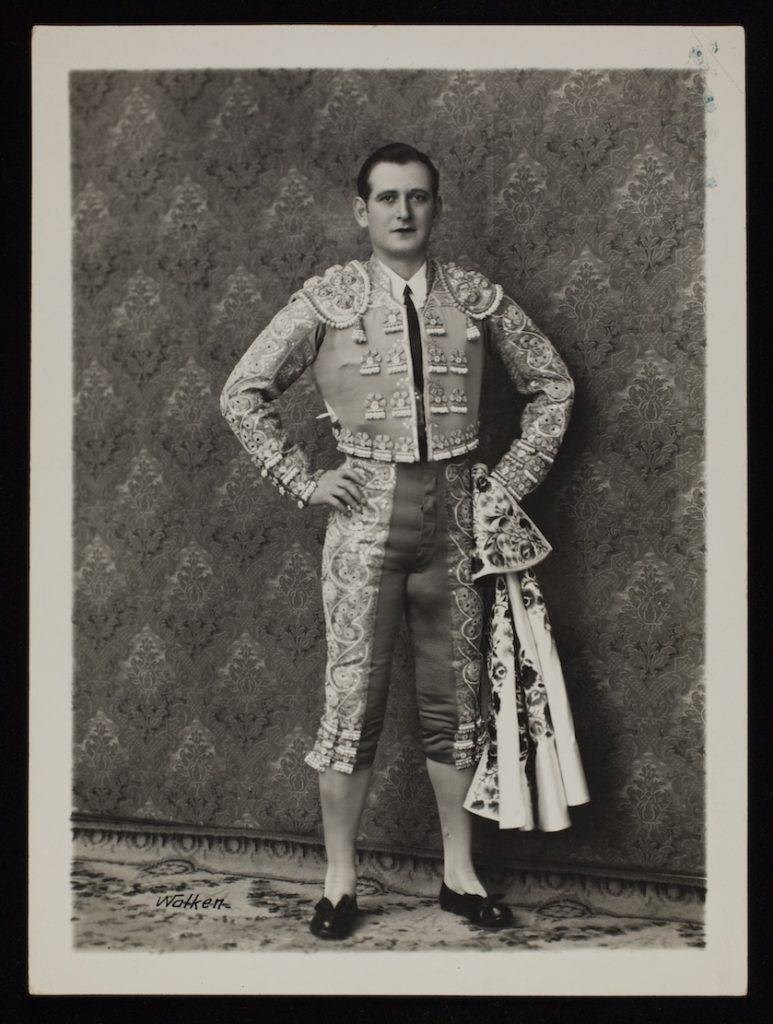

The picture shows him standing in a bullring, wearing black slippers and a suit with sleeves bedazzled in curly, floral embroidery. Smiling, Franklin hugs another bullfighter with both arms wrapped tight around the fellow's back, his left hand a half-inch above the man's butt.

"I identify as a lesbian and a fervent animal lover," said Rachel Miller, the Center's director of archive and library service. "I was stunned by the death and violence that this gay man inflicted on bulls."

The photo is one of 80 items Miller has uncovered to better understand the life of the bullfighter once known by his fans as "El Torero de la Torah."

Miller presented the collection, which features newspaper clippings, records, audio recordings and photographs, during a lecture at the Center for Jewish History on June 3.

Something Miller learned early on in her research: Franklin was in the closet until his death on April 26, 1976. His sexuality was an open secret among family members and in the Spanish bullfighting community, according to Bart Paul's biography of Franklin, Double-Edged Sword: The Many Lives of Hemingway's Friend, the American Matador Sidney Franklin.

He was also fabulous; he mingled with the rich and famous, including Hollywood actors Douglas Fairbanks and Paulette Goddard.

His close friend Ernest Hemingway wrote about him in Death in the Afternoon: "You will find no Spaniard, who ever saw him fight, who will deny his artistry and excellence with the cape."

A three-part New Yorker profile on Franklin by Lillian Ross in 1949 details his wardrobe of nine matador suits, each worth up to $2,000. "Franklin owns the most splendid and expensive wardrobe in the profession," Ross wrote.

"He knew, as a gay man, that there were terrible prejudices about him in the world. He also knew, as a Jewish man, that there were terrible prejudices about him," said Franklin's 78-year-old niece, DorisAnn Markowitz. "He confronted that by being larger than life."

Markowitz remembers him from growing up in Marine Park. Franklin stayed in her mother's basement whenever he returned to New York and would bring his bullfighting suits with him.

"He would take a jacket off the hanger and put it on me, and I would collapse because it was so heavy," said Markowitz.

Franklin was born Sidney Frumkin in Park Slope on July 11, 1903, to Russian Orthodox Jewish parents. Drawn to theater and art, he acted in plays while attending school and assumed the stage-name "Franklin" to evade the eye of his father, a policeman who did not approve of his son's hobbies. Franklin dropped out of high school and began a commercial art business.

"Uncle Sidney was the one child in the family who was picked on more than any other by his father," said Markowitz. "He was the child that got beaten more than anybody else."

When he was 19, Franklin spent a secret weekend away in Asbury Park, New Jersey, with a man who, according to Miller, may have been his lover. When Franklin returned home, his father beat him unconscious.

The next morning, Franklin woke up, packed his belongings and boarded the SS Monterey, bound for Mexico City.

Franklin continued his commercial art business in Mexico, selling fliers for bullfighting events. The first time he watched a bullfight, he claimed to be unimpressed.

"I fumed over my impotence to stop this wanton brutality," wrote Franklin in his autobiography.

According to Franklin's account, after a feud with two Mexicans who said Americans lack the courage to be bullfighters, he met with Rodolfo Gaona, a famed torero of the time. Franklin trained under Gaona in Mexico City, where he made his bullfighting debut in 1923.

Researching him, Miller said, it was difficult to parse fact from fiction in Franklin's book. Franklin had a penchant for telling tall tales, for better or worse, so she had to fact-check with surviving relatives and through Paul's biography. Markowitz estimates half of it is exaggerated, and half of what's exaggerated is likely made up.

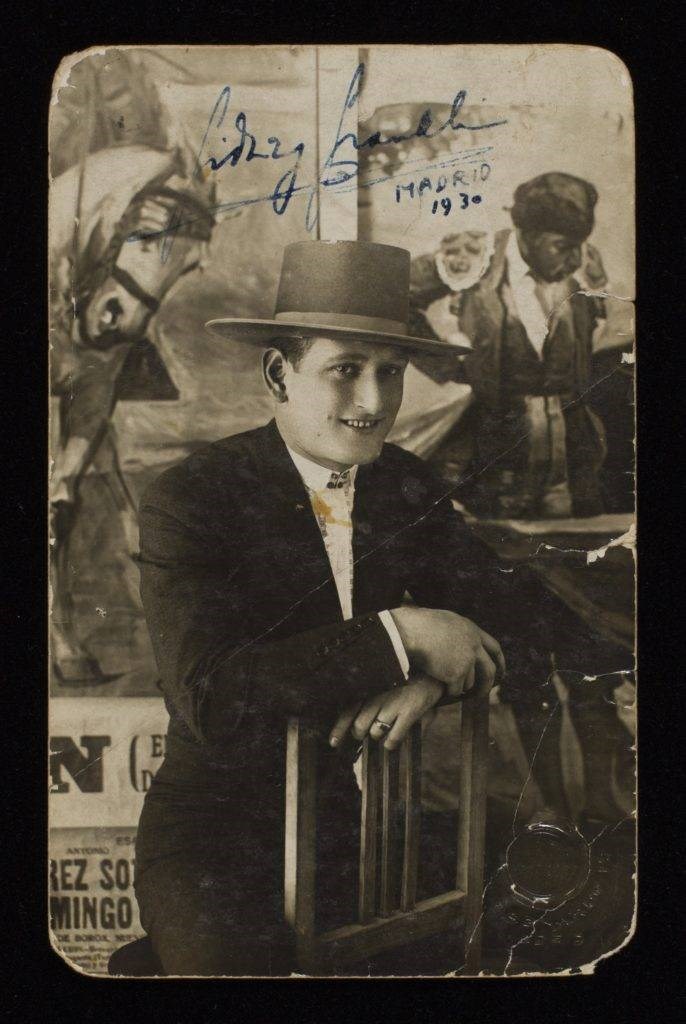

In June of 1929, Franklin made his Spanish debut in Seville. After the kill, the crowd cheered and carried him out of the arena on his back.

He continued to kill bulls across Spain every Sunday until a few injuries — he was gored once in the rear and gored again, later, on the thigh — signaled the end of his career.

As for why a closeted, gay man would turn to bullfighting, Miller thinks the glittering costumes, flamboyant performances and roaring crowd provided a way for Franklin to prove his masculinity, express a queer sensibility and luxuriate in the approval his father never gave, all at the same time.

"I see it as a really interesting way of both masking his homosexuality but performing it as well," said Miller.

Bullfighting may have also provided a vehicle for him to pass his trauma — from his physical abuse and from being closeted — down to the animals.

"I truly believe every time he fought a bull, that bull was his father," said Markowitz.

At the end of the Out of the Box lecture, Miller took questions from the audience.

"Given he was closeted, how do you think he would feel about us talking about him for Pride month?" an audience member asked.

"I think, if he were alive today, he'd be at the front of the Pride parade," said Miller.

The Sidney Franklin Collection can be viewed online and at the American Jewish Historical Society.

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)