A new Harvard study finds that 40 percent of black boys who are raised wealthy end up poor as adults. Why?

Dear Brooklyn Readers,

A recent study, led by researchers at Stanford, Harvard and the Census Bureau and published on Monday by The New York Times, revealed that 40 percent of black boys raised in America in wealthy families will end up as lower-class or poor adults. Interestingly, the study also noted that black and white girls from families with comparable earnings attained similar individual incomes as adults.

Researchers asserted that black boys are more sensitive than black girls to disadvantages like growing up in poverty or facing discrimination. Based off the study data, and the more optimistic outcome for black girls, the writer concluded that the overall income inequality that exists between blacks and whites "is driven entirely by what is happening among these boys and the men they become."

This data is momentous, the article is compelling and The Times's graphic illustrations are exceptional. But I have a problem with the passive-aggressive argument this article suggests: that, although racism disproportionately targets black boys, it must not be that damning if no difference in outcome is reported among black girls. And, furthermore, black men-- versus racist institutions-- are entirely responsible for the disparity in black family wealth.

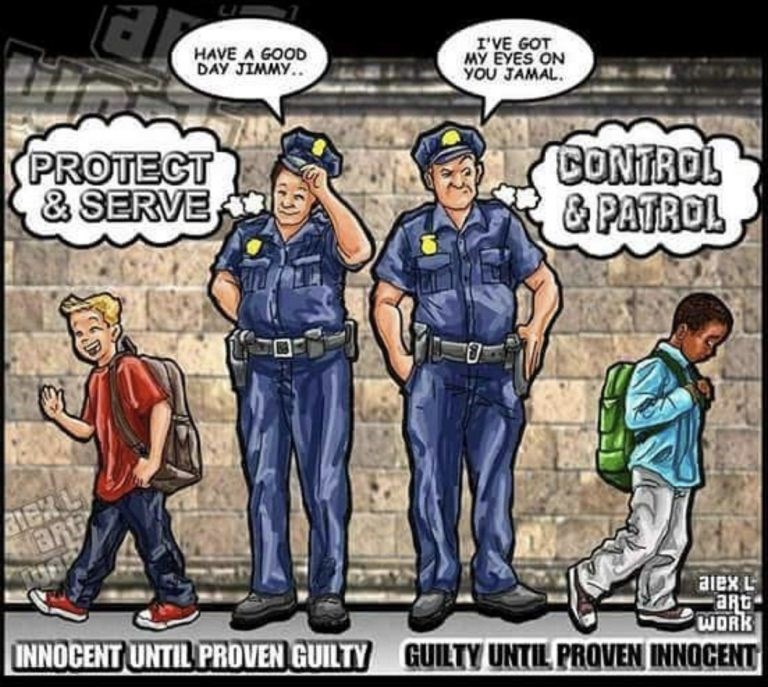

One week ago, Stephon Clark, a 22-year-old unarmed black man and father of two, was shot and killed by the police in Sacramento for being a suspect of loitering in his own backyard. This young black man did not die not because he was "sensitive" to racial profiling. He died because of it.

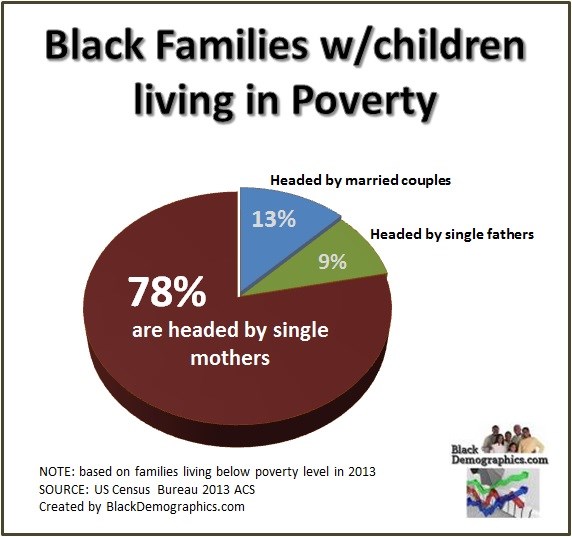

Generations upon generations upon generations of racial profiling, mass incarceration and paternal poverty have had a devastating effect on not only black men but, also, black families. The two are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are inextricably tied.

Black women do better, not because they do not experience racism. They do "better" because they have had no other choice. Beginning with American slavery, black women have been preparing their girls to shoulder the load alone, unsure of the male's future: He might end up unemployed, underemployed, off somewhere trifling, incarcerated or dead.

I highly doubt these are thoughts that occupy the minds of white women and little white girls about white men. But as a black child and now a woman, this was my reality and continues to be the reality for most black women I know. I can share many examples, but I will start with just one:

In 1978, my single mother, along with my two sisters and I, became the first black family to move into a quiet suburb of Chicago through a housing voucher program called Gautreaux, a result of a lawsuit around Chicago's racially segregated housing policies. We were very poor. My father was incarcerated, and my mother was on a solo mission: to get a piece of everything formerly unavailable to us in the housing projects.

Summer track camps? Her girls were doing it. Free clarinet lessons? She'll take it! A new children's play at the local theatre? Her girls were auditioning. Scholarships to horseback-riding camp? She was signing us up! Racist teachers? Work harder. Racist classmates? Be smarter. The pressure...

We didn't understand it then, but she was preparing us for an adult life where, as women of color, we'd be denied access often. And so her ultimate aim was to widen our options through as much education as possible.

We were advanced students when we lived in the projects. So when it was time to take the gifted and talented exam at our new suburban school, she signed us up for that as well. When we didn't make it into the program, my mom pitched a fit! "What do you mean my girls didn't get in?" she argued to the school's principal. "My girls are gifted and talented too!" Even after the principal showed her the test scores where we fell short, and even after the program started without us, my mom would not relent. She insisted we were let into the program. She complained, complained, complained until finally, the principal, exasperated, told the instructor to let us in.

I remember walking into my first G&T session feeling entirely embarrassed and out of place. I was the only black kid in a room full of Asians and towheads, and I was completely lost. The teacher, annoyed I was let in, rarely made direct eye contact with me. Twice a week we would meet. Twice a week, I would just sit there silent. And twice a week, the teacher completely ignored me until, eventually, the kids did too. Why did my mother do this, I thought? Why was she always so forceful? Clearly, I didn't belong.

Half-way through the school year, I continued to show up and continued to pretend I was invisible. Until one day I thought I knew the answer to a question, so I blurted it out. And I was right! Then, in the next session, I tried to answer another question. I got it wrong. But my confidence was building. After about 6 months, I was answering a lot of questions. Some I got right; others I got wrong. But now, I was fully participating. By the end of the year, not only had I caught up to the other kids, I had grown competitive.

The teacher never stopped turning her back on me. She continued to ignore me, even after I caught up. Because, ultimately, it wasn't about my aptitude, it was the fact I allowed into a space I was never "supposed" to be in the first place. This is America-- a place where opportunity for advancement and access to resources are divided along racial lines. Those who manage to cross the lines will enter environments where they are treated as someone unwanted or somehow undeserving.

My mother pretty much forced us into that program, as she did all of the programs back then. But would she have pushed her boys so hard? Furthermore, would the principal have been so forgiving if we had been black boys? According to research by the Yale Child Study Center, the answer is "no."

The study found that teachers, beginning in preschool, hold implicit biases against black boys. They routinely lost valuable class time watching out for disruptive behavior in black boys where none existed to any less or greater extent amongst their classmates. So, not only is authority less forgiving to black boys, it is more punitive.

And what happens when they become young men? Numerous studies have shown that black men are disproportionately targeted, stopped, frisked and searched through the practice of racial profiling. Black men end up in prison more often, receive longer sentences than similarly situated white men and are 21 times more likely likely than white men to be killed during police encounters.

Forty percent of wealthy black boys end up tumbling back to the bottom of the income bracket! This statistic is far more than some notion we mull over, it is absolutely and utterly tragic! So let's stop pretending we're not entirely clear about why. It's not because they're "sensitive" to racial discrimination; it is because they are its direct target. This uphill battle to access opportunity, build and maintain wealth, and create personal stability has had far-reaching effects on their life choices, their mental health, their women, their little girls, their little boys, their families, their entire community.

America's not off the hook just because black girls fare better. The only reason they fare better is because, Black mothers, consciously and unconsciously, prepare their little girls for a life of racism, sexism and having to handle it all. It is stressful and exhausting.

Where maybe an inch more may be given to black girls over the black boys, the girls already have been training to run a mile.

Sincerely,

C. Zawadi Morris, Editor and Publisher