Fifteen years after the city reached a settlement with New York City health activists over the spraying of pesticides to counter the West Nile Virus, those same activists are still fighting for the spraying to stop.

After a recent spate of sprayings across the five boroughs in September, including in the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Williamsburg, Bushwick and Greenpoint, members of the No Spray Coalition have raised the alarm once again.

"Our goal has always been to make it stop, I can't believe how many years it's been going on with no substantive review of it," No Spray member Cathryn Swan, a Kensington resident, told BK Reader.

The DOH says its data-driven approach to mosquito control has "successfully helped control mosquito-borne diseases since the West Nile virus was first detected." It says it relies on mosquito trapping and testing results to determine areas of the city to spray pesticide and apply larvicide by helicopter, truck or backpacks.

However, the No Spray Coalition says the approach has never been properly reviewed by any city agency despite the continued use of toxic chemicals.

They say there is no evidence that the number of mosquitoes has diminished through pesticide spraying, and point to studies that state that mosquitos become resistant to the pesticides and come back in larger numbers after spraying.

Swan got involved with No Spray in 2000 when the Guiliani administration started spraying pesticides and it was covered in the New York Times. "I was reading an article about how it affected every layer of the ecosystem, even insects would be affected. That really resonated with me, the harm to other species," she said.

The pyrethroid pesticides being sprayed—including Anvil 10+10 and Duet—have been shown to be harmful to human health and the health of the eco-system, including animals, birds, bees, and other insects, the coalition says.

"People don’t realize it's a truck coming by with a big fogger—it's almost surreal—fogging a huge plume of toxic pesticides," Swan said.

The coalition says the pesticides also kill off natural predators of mosquitoes, including dragonflies and bats, and are not proven to decrease the mosquito population.

However, the NYC Health Department (DOH) told BK Reader the department uses "very low concentrations of Anvil® 10+10 or Duet®."

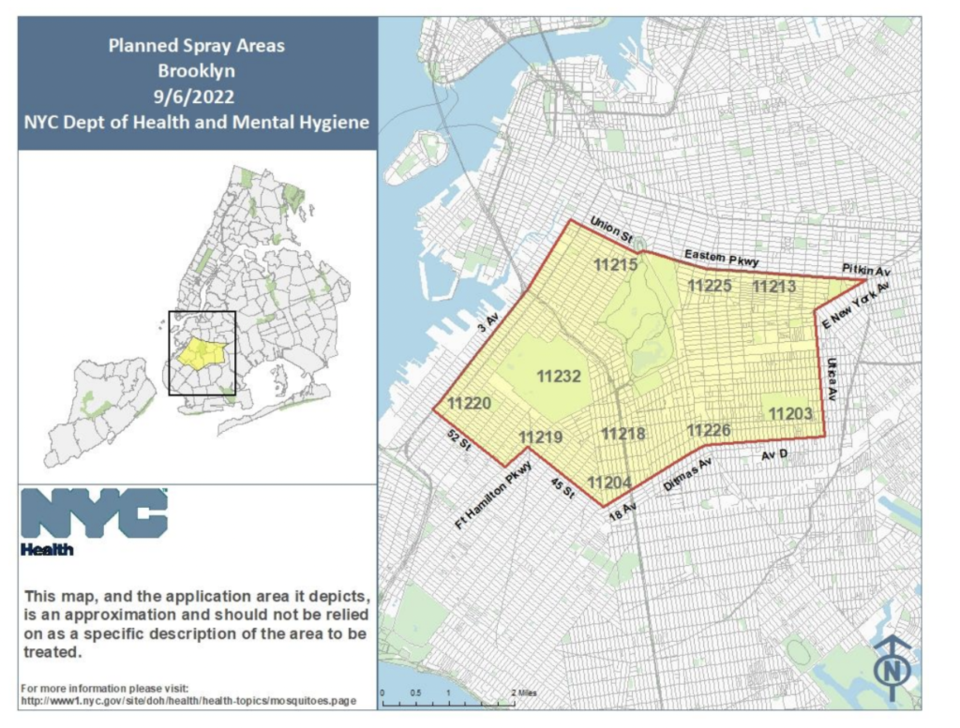

The city has done seven spraying events in Brooklyn this year, with misting done in Bushwick, East Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Cypress Hills, East New York, Borough Park, Brownsville, Crown Heights, East Flatbush, Flatbush, Gowanus, Greenwood Heights, Kensington, Little Caribbean, Little Haiti, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, Park Slope, Prospect Park, Prospect Park South, South Slope, Sunset Park, Windsor Terrace, Bath Beach, Bay Ridge, Brighton Beach, Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Dyker Heights, Fort Hamilton, Gravesend, Manhattan Beach, Sheepshead Bay, Bergen Beach, Canarsie and more.

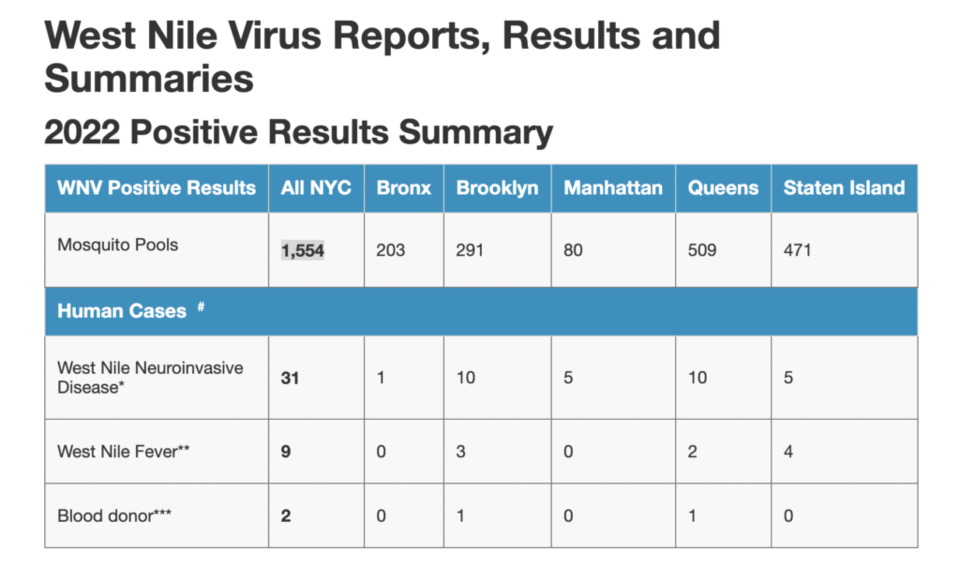

West Nile virus was first detected in New York City more than two decades ago, according to the City. Over the past decade, an average of 16 people have been diagnosed with West Nile neuroinvasive disease per year in NYC.

Their median age was 62 years and the case fatality rate was 14%, or 23 deaths.

In 2021, a new pesticides bill passed the New York City Council, intended to reduce the use of pesticides. However, the DOH is able to issue itself waivers to the bill, in the interests of public health.

"The risks of pesticides applied by the Health Department for mosquito control are low to people and pets," the department said. "West Nile virus, however, can cause very severe illness, and those older than 60 are at highest risk."

According to DOH statistics, there have been 31 cases of West Nile disease recorded with neuroinvasive symptoms (brain swelling, paralysis or meningitis) in New York City so far this year. Ten of those were in Brooklyn.

However, according to Mitchel Cohen, author of The Fight Against Monsanto's Roundup, while the entire borough of Brooklyn is routinely sprayed, he said the practice disparately impacts people of color presenting higher rates of respiratory illnesses like asthma. He said the city needs to begin an alternate approach focusing on picking up trash more frequently, clean water, and the use of natural predators like dragonflies.

In 2000, No Spray sued the City for the pesticide practice. In 2007, the City settled the lawsuit, paying $80,000 to environmental groups and signing a document admitting that the pesticides may stay in the environment beyond their intended purpose and may cause adverse health affects, Swan said.

The city was also required to state that the spraying does kill mosquitos' natural predators, and increase their resistance to the sprays.

The DOH did not respond to specific questions about the admissions made in the settlement.

However, in its 2022 mosquito surveillance and control plan, the city said it was monitoring the impact to human health through tracking visits to hospital emergency departments and monitoring for possible respiratory symptom related clusters.

Meanwhile, the DOH advises residents to stay indoors during the spraying—typically done between 8:30pm and 6am—but says air conditioning units can remain on. Notices on the spraying are typically released to media and community leaders two days before an event, it said.

"Some people who are sensitive to spray ingredients may experience short-term eye or

throat irritation, or a rash. People with respiratory conditions may also be affected," the most recent notice states.

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)