At 19, Russell Frederick got his first studio apartment in Bedford Stuyvesant for $425 a month. It was the late 80s, and the neighborhood was not a desirable place to live.

“In the 80s and 90s, nobody wanted to come to Brooklyn,” said Frederick, who grew up in Bushwick.

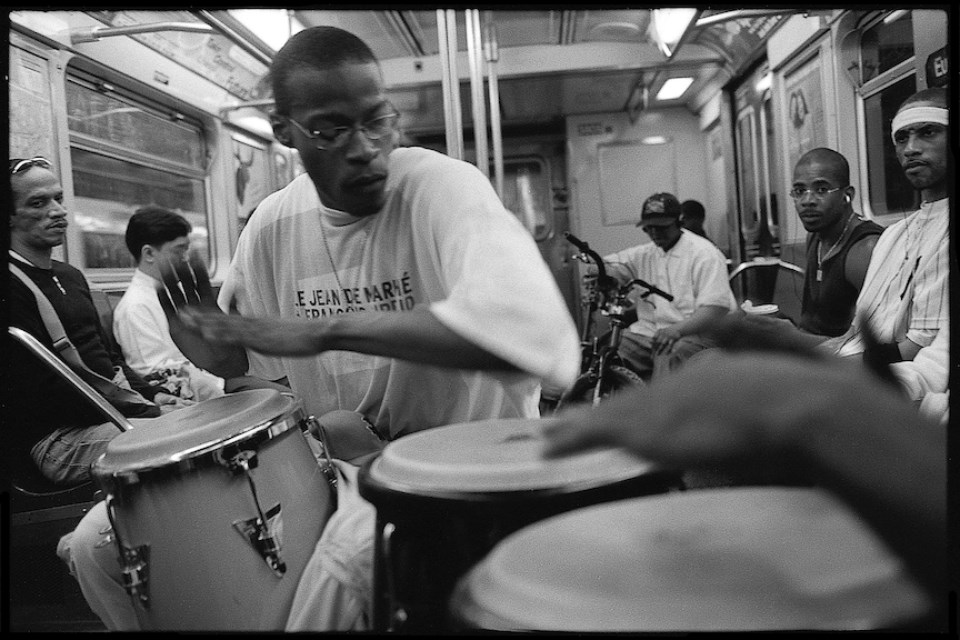

Frederick, who's current home studio is on the ground floor of a classic Brooklyn brownstone in Bed-Stuy, has spent more than 25 years documenting the neighborhood and its residents through his striking black-and-white photography.

Now, the prolific photographer, who has been struggling with vision loss since 2015, is facing potential displacement from the home studio he lives and works in.

Passion for His Community

Frederick first fell in love with photography while studying to become a nurse. He turned to the medium after becoming dismayed with the politics of the healthcare field.

“I saw that healthcare wasn't about really the patient; it was a lot more about the business and the politics of it,” said Frederick. “I felt that I had a bigger calling than being of service as a nurse. And I also had a gut feeling that I was supposed to do something artistic.”

After taking a photography class at the International Center of Photography in 1997, Frederick decided to pursue photography full time. “I was 27 and I never looked back.”

He looked to his neighborhood for inspiration. Frederick’s goal was to capture Black people and the people of Bed-Stuy in a more authentic fashion than he’d seen before. He wanted to show that the neighborhood had more to offer than its negative stereotypes, which centered around violence and poverty.

“I started to focus on Bed-Stuy, because I wanted to change the way the world saw my community,” said Frederick. “Walking the streets, what I saw was not what I had read about Bed-Stuy.”

In the early days, Frederick would stand with his camera and light meter on the corner of Bedford Avenue and Fulton Street and strike up a conversation with people he wanted to photograph. He used black-and-white film to develop his signature style.

Even in the late 90s, Frederick said he anticipated the negative effects of gentrification on the historically Black community of Bed-Stuy.

“I knew I had to honor all of the good people who made up this community before they got priced out," he said.

After becoming known for his work, Frederick went on to photograph in foreign locations, including Ethiopia and Jamaica. His work has been displayed in galleries in Europe, Asia and Africa; and he has taught as a guest lecturer at New York University, the School of Visual Arts, Columbia University and elsewhere.

“I saw how my camera could uplift people ... I saw how my camera can make some people smile. I also saw how my camera could also make some people nervous, and how my camera could be a reflection that some people weren't always comfortable with," he said.

Sudden Loss

When Frederick learned that he had a detached retina and a form of glaucoma in 2015, doctors told him some of his vision could be restored. Within the first year, he had three eye surgeries. By 2017, he was completely blind in his right eye.

At a follow-up visit, his ophthalmologist told him there was nothing further that could be done for his vision loss. For the photographer, this bleak diagnosis felt like a “death sentence.”

“I had to start using some other senses to kind of overcompensate for what I was losing in vision,” Frederick said. “The hardest part was just daily functions that I used take for granted, like reading the newspaper, opening up some mail, reading the back of a food label.”

Glaucoma is an eye disease that typically has no symptoms on onset. It effects Black and Latino people at much higher rates than whites. According to a 2022 Mount Sinai study, Black patients are six times more likely to have advanced vision loss after a glaucoma diagnosis than white patients.

After spending half of his life taking photos, losing a large portion of his vision called for a major adjustment in how Frederick worked. He adapted by using digital cameras and the autofocus features.

“[Vision loss] has made me develop skill sets with digital photography, shooting more in color, as well as certain editing techniques on the computer,” he noted.

A Fight For The Future

A decade into his battle with glaucoma, the impact of his vision loss on his ability to work has begun to add up. Numerous surgeries and long recovery periods have caused Frederick to miss out on work opportunities over the years, creating serious financial instability.

Now, the die-hard Bed-Stuy resident may soon be displaced from the community he’s dedicated his life to reflecting. After falling behind on rent and facing a rent increase, a friend of Frederick’s has decided to launch a GoFundMe campaign to help him with back rent and moving expenses.

“To not be able to take care of some of your needs is not something that I wish on anybody,” said Frederick. “The Black and brown people who made this community what it is deserve better. Some laws must be passed to preserve and protect the long-term homeowners and renters, so Bed-Stuy does not turn into Park Slope.”

Frederick still plans to complete his most important project, compiling more than 10,000 photographs of Bed-Stuy into a book.

“To publish the work will be one of the happiest days of my life,” he said. “So many people have trusted me with their images over these 25 years. I have to honor them and show the world this visual journal of soul that is Bed-Stuy.”