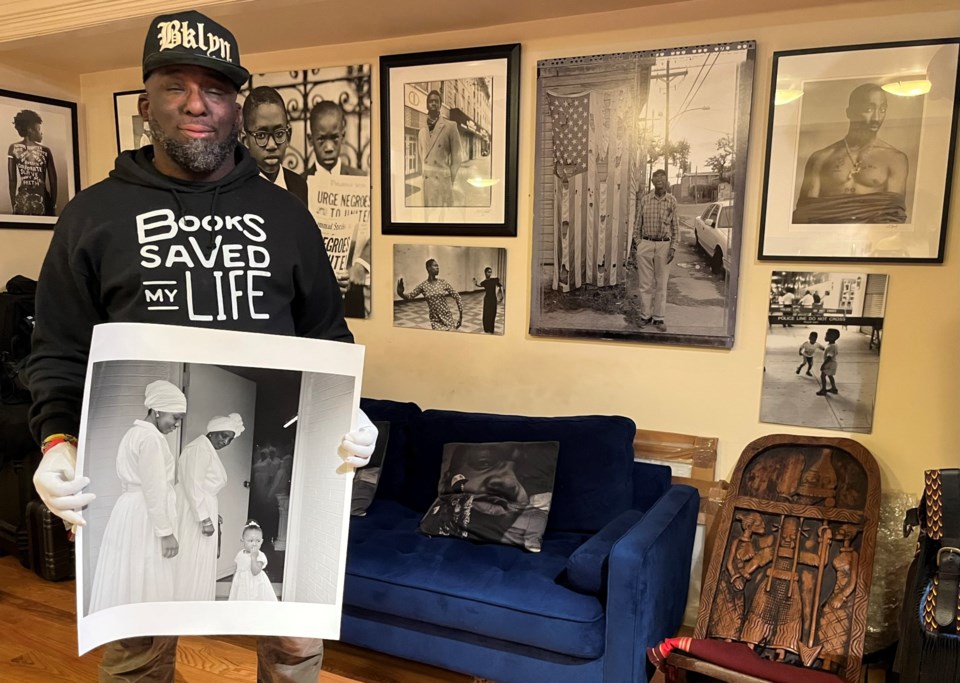

Bed-Stuy resident and photographer Russell Frederick has been capturing timeless moments across Brooklyn for the past 25 years. His work has been featured everywhere, from NPR, to The Washington Post, to Ebony Magazine.

BK Reader first profiled Frederick, eight years ago, while he was working on “A Love Letter To BedStuy," a photo documentary championing the resilience of the residents of Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. At the time, he had already collected more than 10,000 photos.

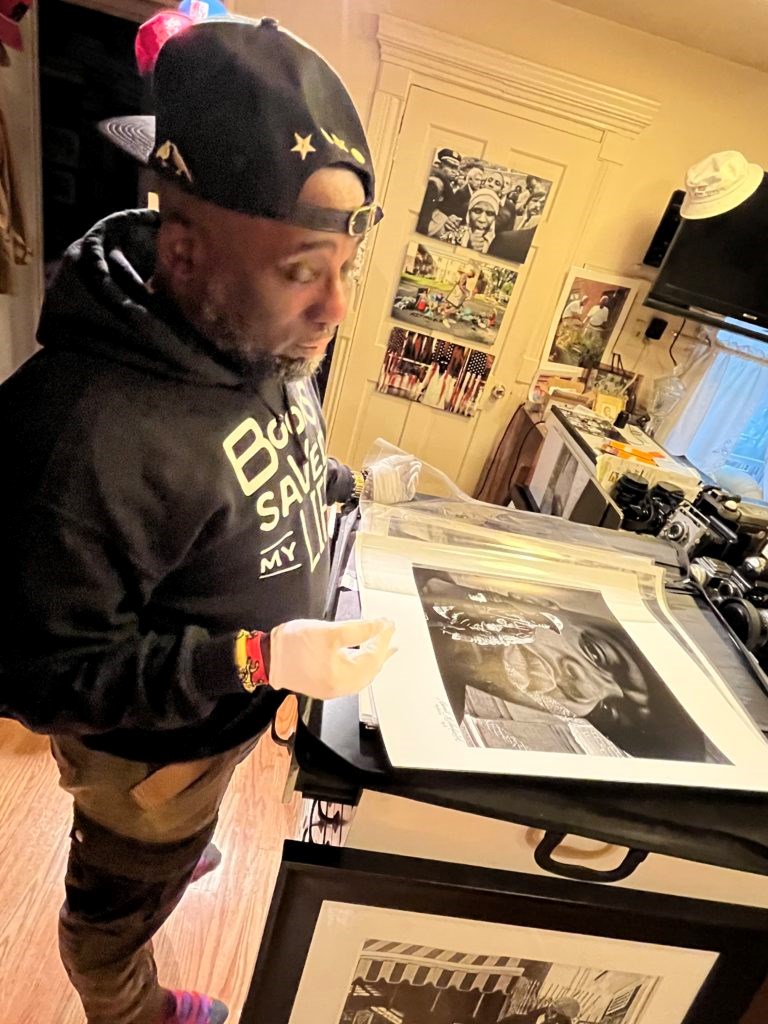

Photo: Natasha Knows, BK Reader

BK Reader most recently caught up with the photo warrior in his studio to learn about the latest major changes in his career and life, including a nomination for the highly esteemed W. Eugene Smith Grant for Humanistic Photography, a life-changing health diagnosis, and a new lens on his work.

For the grant, Frederick was one of eight nominees selected from over 400 global submissions. Although ultimately, he was not awarded the grant, “to be a finalist is a big deal because a lot of museums, publishers, editors, the industry as a whole really respects this award,” says Frederick, “which often leads to book deals that catapult a photographer’s career in the top tier of this industry.”

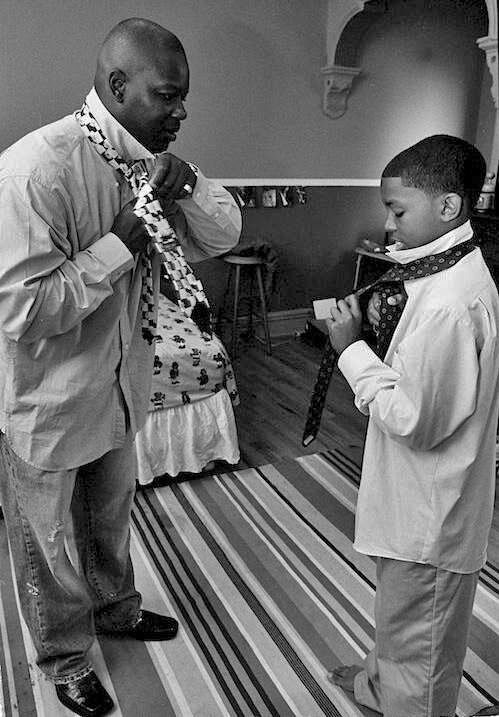

Frederick, a member and former vice president of Kamoinge, a collective of Black photographers, has always been most interested in speaking to the heart and soul of Brooklyn:

“Brooklyn is now a vogue place to be,” he says while removing the white gloves he wears when handling his photos. “It was once depicted as the slum and had a notorious reputation. But in that toughness, it’s a place where steel sharpens steel.”

Photo: Russell Frederick

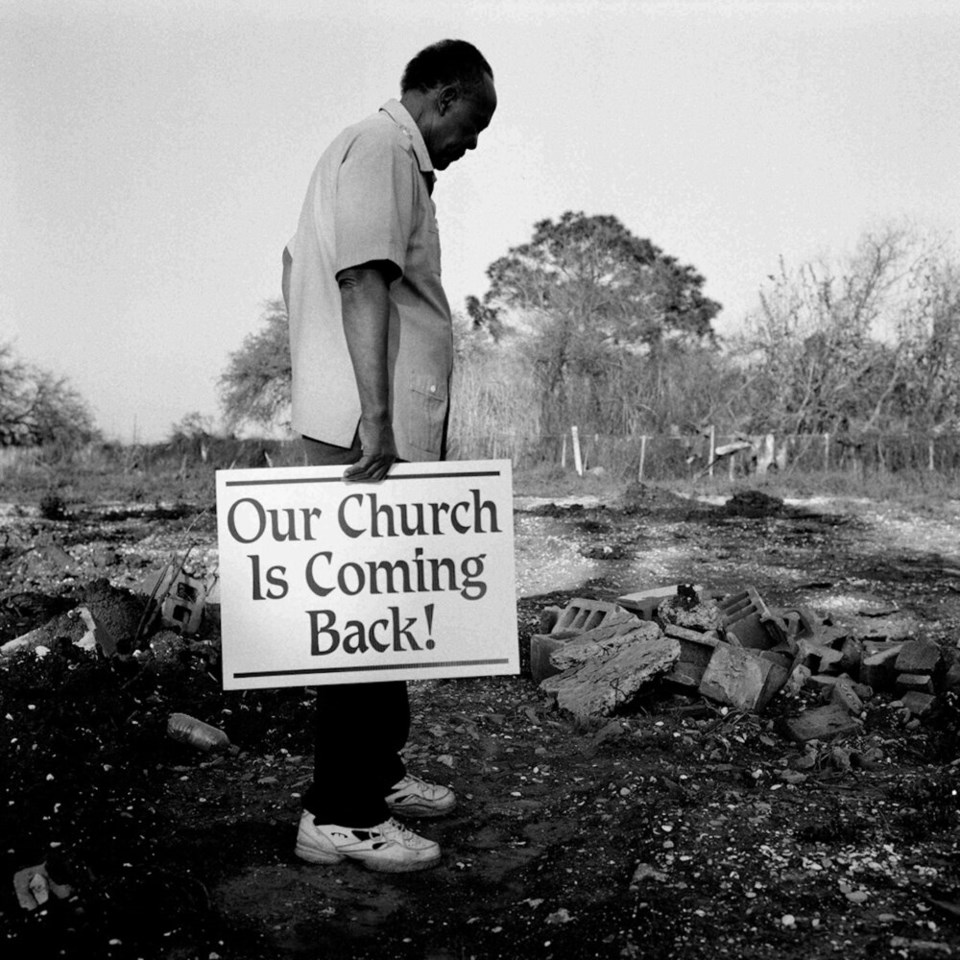

Photo: Russell Frederick

New Orleans (2007)

Photo: Russell Frederick

The famed photographer has covered the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, captured the ravage of COVID-19 in Brooklyn, and even flew out to Minnesota to shoot the visible rage of George Floyd’s death.

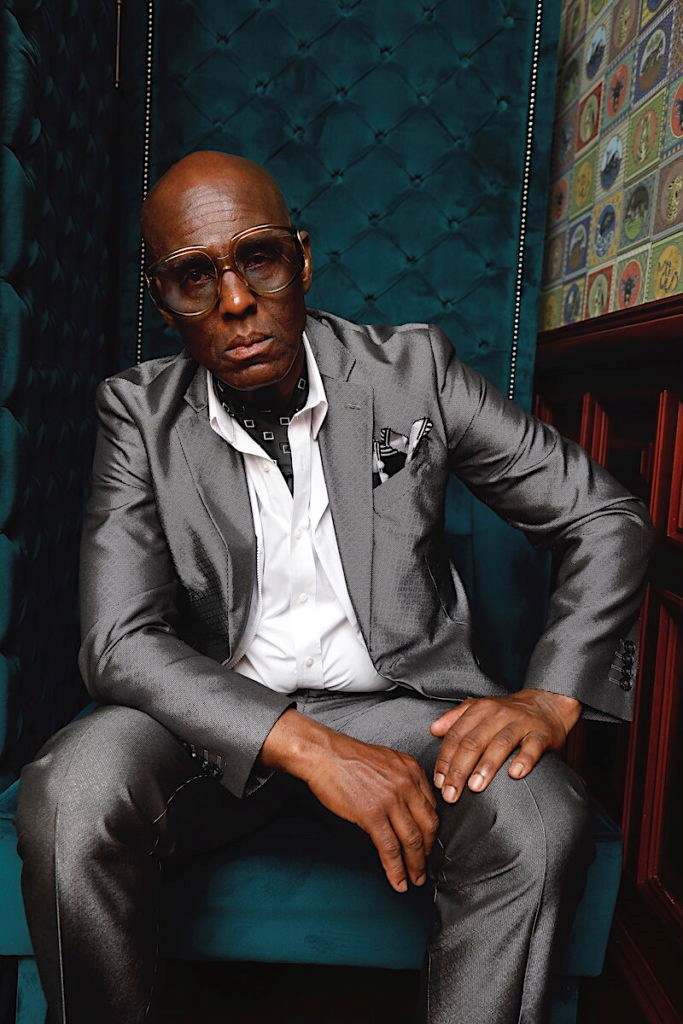

Still, nothing could have prepared him for the most shocking news of his life. After multiple optical surgeries to repair a detached retina, Frederick was diagnosed with a very aggressive form of glaucoma.

“Things started changing very quickly, my vision never restored, and finally the doctor told me there’s nothing else we can do.” He continues, “I was in complete shock, I’m a visual activist, my eyes tell the story of the world.”

Russell Frederick

The diagnosis brought an onset of depression and concern for his future. His world was growing dark. Literally. As one eye slowly went blind, the peripheral vision in the other was limited.

Imagine the frustration of having blurred or fuzzy lens on your camera that you cannot wipe off but, instead, that camera is your actual eye.

Frederick had two options: Either give up photography-- his lifelong passion-- or adjust to his new limitation of seeing the world now with one eye. He started to learn braille, while working on sharpening the acuity of his other senses.

“As I still continue to make photos, I have embraced the other visual languages of storytelling in curating, producing, directing and more.”

Harlem (2018)

Photo: Russell Frederick

Minneapolis (2020)

Photo: Russell Frederick

Harlem (2018)

Photo: Russell Frederick

Frederick notes that while he still photographs BedStuy in B&W film he is also currently embracing colorwork using digital photography and the autofocus feature: “I’ve had to unlearn the way I used to make pictures and move through the world so I could unlock this next level of growth and creativity on how I now see the world with one eye.”

Currently, Frederick is photographing a project for ESPN. He's also working alongside Anderson Zaca in The Darkroom Masters, a series showcasing some of the most underrepresented names in photography.

Also, he is scheduled to be a guest lecturer on photography at Yale University this winter.

“When you find out you have an issue you can’t fix it’s the scariest sh-t ever, but I am determined.” He continues, “I have a responsibility to all those people who trusted me with their image.”

Frederick plans to turn “A Love Letter To BedStuy” into print form soon: “I’m redefining how the world sees us, the journey to inspire people and challenge everyone to be a little more humane towards each other," he adds, "You never know what people are going through.

"I realize I gotta move a little bit differently. I lost my sight but I haven’t lost my vision!”

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)