By: Thomas Goldring, Georgia State University and Tim R. Sass, Georgia State University

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to substantial reductions in student learning in metro-Atlanta public elementary and middle schools. What's more, these impacts have grown over time, according to our new research.

By winter of 2020-21, we found that average math achievement within a grade was up to seven months behind where students likely would have been had the pandemic not occurred. In reading, students were up to 7 ½ months behind on average in some grades.

Students often fell further behind between the fall and winter tests, sometimes dramatically so. The effects of the pandemic varied by subject, grade and school district, complicating how districts can determine their responses to this unprecedented disruption to formal education.

We also found that the pandemic often made preexisting disparities worse.

For example, students eligible for free or reduced-price meals — a crude measure of poverty — generally experienced slower achievement growth during the pandemic than did ineligible students. Similarly, traditionally marginalized student groups, including Black students, Hispanic students and English learners, generally experienced larger reductions in achievement growth.

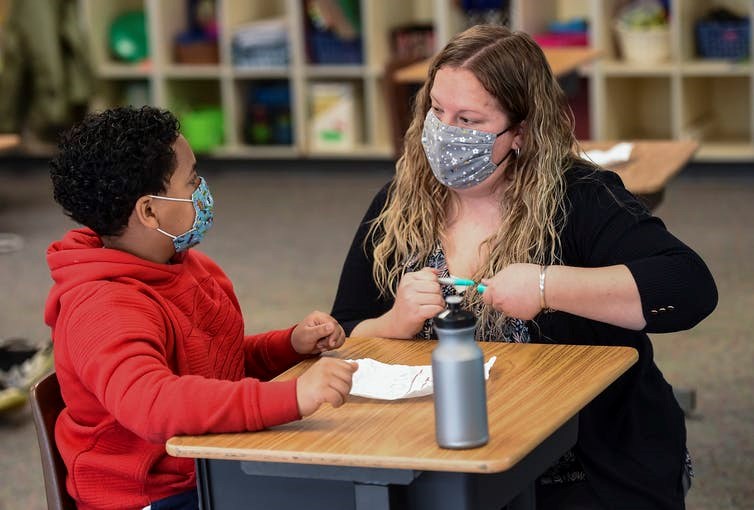

We wanted to understand whether the return to in-person learning would reduce the harmful effects of the pandemic. Elementary school students who returned to in-person instruction in the fall of 2020-21 experienced greater achievement growth per instructional day than students who continued to learn remotely, but their growth was still less than for comparable students before the pandemic. This could be due to student difficulty in transitioning back to in-person learning, emotional trauma or other effects of the pandemic. Alternatively, increased disparities in student achievement could make teaching more difficult. For middle school students, differences in the rate of learning between in-person and remote instruction were modest.

Why it matters

Many people are concerned that school closures and virtual learning during the pandemic slowed student learning. Understanding the extent of the slowdown will help districts determine what sort of intervention strategies may counteract the losses, and what resource levels will be required to meet the challenge.

Similarly, knowing how achievement growth varies by instructional mode — remote, hybrid and face-to-face — will inform decisions about the use of remote instruction, both for the remainder of the pandemic and beyond.

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides school districts with funds to help students catch up to where their learning would have been had the pandemic not occurred. The most important implication of our findings is that assistance should be targeted toward students with the greatest reductions in achievement growth during the pandemic.

We recommend that districts use three strategies that prior research suggests have the greatest impact on student achievement.

First, provide high-intensity, small-group tutoring based on classroom content. This strategy comes with the highest price tag, emphasizing the need to focus on students with the greatest need.

Second, extend the school day during the regular academic year.

And third, provide learning opportunities during summer or other breaks, and use incentives like free meals and transportation to increase participation in them.

What's next

Our research group, the Metro Atlanta Policy Lab for Education, continues to dig into the effects of the pandemic on students. We are studying student engagement under remote learning and analyzing how parents chose their student's learning mode. We're also unpacking unexpected findings, such as the relatively milder impacts on girls and students with disabilities.

Thomas Goldring, Director of Research at Georgia Policy Labs, Georgia State University and Tim R. Sass, Professor of Economics, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.