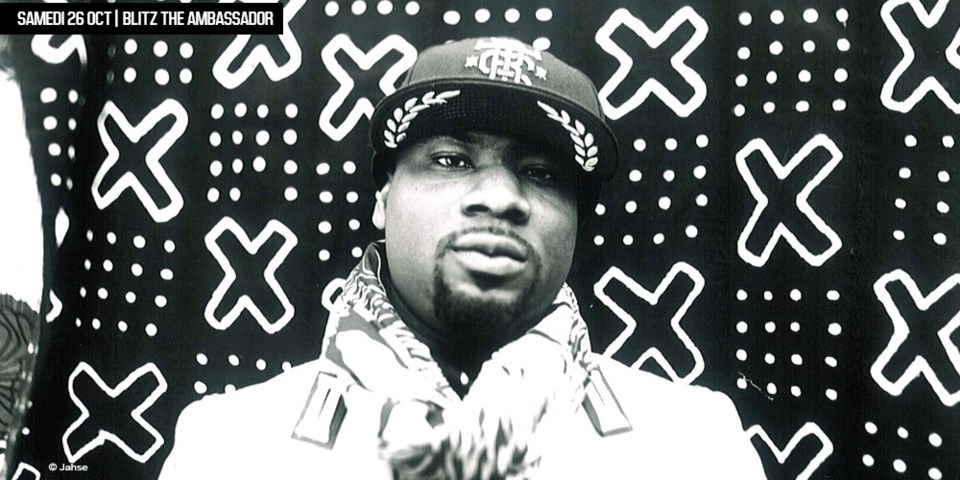

Samuel Bazawule, also known to many as "Blitz the Ambassador," has accomplished a great deal in the past 18 years since moving from his native Accra, Ghana, to the United States.

Samuel Bazawule, also known to many as "Blitz the Ambassador," has accomplished a great deal in the past 18 years since moving from his native Accra, Ghana, to the United States.

Beginning at an early age while in Ghana, Blitz stood out as a talented visual artist, a musician, a soothsayer with a love of hip hop and "the gift of gab." Today, this 34-year-old Bed-Stuy resident has earned a marketing degree from Kent State University; has released three critically acclaimed hip hop albums; is an Okayplayer, and now travels the globe speaking and performing as an ambassador of self determination—his messages, always rooted in cultural awareness and aimed at the youth of the African Diaspora.

On Sunday, July 3, Blitz the Ambassador will headline the 45th annual International African Arts Festival in Brooklyn. Blitz sat down with The Brooklyn Reader recently for an exclusive interview where he shared insight on his Ghanaian upbringing, his love of Brooklyn and the evolving role of hip hop in today's climate of economic uncertainty and socio-political change.

-----------------------*----------------------

The Brooklyn Reader: How does growing up in Ghana inform your direction as a musician and artist?

Blitz the Ambassador: Growing up in Ghana is the foundation and the basis as far as my influences. So for me, I'm Ghanaian first. The issues that I tackle in my music and general aesthetic are all from my upbringing as a kid in Ghana and what I saw and heard, and I go back as often as I can. Young people in Ghana-- and everywhere in the world, really-- are looking for a voice and something to call their own and a way to exert the fact they exist. There are similarities in the struggles between young black youth in America and Ghana. But young people in America are entitled to certain thing, social programs Growing up in Ghana, there was very little entitlement; a lot of mismanagement made it impossible to have social programs that impact young people, and a lot of the young people are frustrated because of this. Also I grew up on a very different sound, which impacts how I create sonically.

BR: You came to the U.S. for your college studies in business and marketing, although you were an artist. Were you planning to head in a different direction?

BA: I chose marketing, because I was clear that I wanted to manage my image, my financials; I wanted to control my narrative in the market. I knew what I was bringing wasn't the norm, and I didn't want to acquiesce that for anybody. I learned branding, advertising, business management, and how to take a product from a rudimentary level and put it into the market.

BR: How has Brooklyn shape you as an artist?

BA: Brooklyn for me was always a mecca, as a hip hop artist. Most of the people I looked up to were either Brooklyn-born or -based. "Fight the Power" was one of the most impactful videos for me. As a kid growing up in Ghana, and as someone from the diaspora, you kind of fantasized about wanting to be a part of this movement, to bring it full circle; you want to land somewhere where the diaspora is strong. I was also fortunate to land in Brooklyn right before the super-hyper gentrification. I only mention that because it was important for my socialization, because I was living a block away from black bookstores and Bread Stuy, which are no longer there. Terrence Nance, a fantastic filmmaker, Gregory Porter, we all used to hang on this one block. That's what community was like for me. We had spaces where we could grow, evolve and learn from each other, that community was a major asset for me, and being able to take elements from that back home. That was the Brooklyn that I embraced and embraced me when I got there.

BR: America is experiencing a lot of turmoil and change lately. It seems more and more, artists are stepping up to speak on social change. You've always been an outspoken artist, as far as how you've positioned yourself socially. Do you feel this is important for more artists to do? Can it really have an impact?

BA: We're losing a great deal of the legends that inspired us. A lot of us got into music because of the artists that inspired us. Now we're beginning to see that there's a real void. Because the discrimination and oppression we experience is not always overt, artists have been able to hide behind whatever to avoid these conversations. But social media has made it so that less and less artists are able to hide because they have to respond to their fan base. So if this is what they're fan base is tweeting about, they have to step up to some extent. We're shedding that label that only conscious artists have to speak about these issues. We're going to a place where we all can acknowledge that these issues affect all of us. My thing is figuring out a way to get to young people, whether it's on a volunteer basis, ongoing basis or semi-permanent basis. They are the most vulnerable minds. Wherever I speak or perform, I try to make sure there's some type of forum where young people can gather and be heard. I think it's important we show young people that success comes in different forms. My success is different from Beyonce's success, but it's no less valid. Young people need to see that.

BR: What advice can you share with young people about overcoming personal challenges?

BA: I can really only speak on this issue from a space of a creative, because knowing where you fit in this whole patchwork is critical. One of my go-to's as an artist is Toni Morrison, as a thinker, a phenomenal woman and oracle. Her writing is a constant reminder, as an artist of color, that we have an important role to play. That role is one where we have to deal with whiteness as something that must be navigated, this idea of constantly having to defend your right to exist. And although it's not discussed, it's something we're constantly dealing with on a deep level, as soon as you leave your home. Because as much as we're dealing with aggression against black bodies in America, I see it in Brazil and on the continent as well.

The key is we cannot stop our work and stop what we're doing to prove that we're worth being here. I'm a supporter of dissent and disruption. But I think it's important we find community and purpose in the work we do, because there's a gaping whole in a lot of us as people of color that we're hoping we can fill by white acceptance—whether it's the Oscars, the media We have to understand that we are enough, and that "enough" comes from community.

The most important thing I've done to help me get through personal challenges is to find community in Diaspora and hold on to the most important elements. There's so much that we can learn from and build from each other, which in a way is my place of sanity. We also have our internal problems. So we need to start building our internal gaze, and stop waiting on this external gaze to tell us what to do and just deal with our problems. If we can see the positive of that and see how we can cultural exchange our internal growth and maintain a certain sense of identity, I think a lot of these mental and psychological issues will subside.

BR: You are performing at the African Arts Festival next month. What does that festival mean for you as a chosen performance venue?

BA: It's a big honor. I've been an attendant of the festival for several years. So I know it's a space where we come to engage with one another and to heal. When you're there and see the level of respect and reverence for one another, I know it's the audience I need to speaking to—an audience that speaks to Diaspora work, which is very important to me as a Pan-African artist.