Few will argue the tremendous impact award-winning novelist and short story writer Edwidge Danticat has made on the contemporary, literary landscape over the past 20+ years.

Her fiction and non-fiction work has provided a distinct and palpable narrative around self-realization and self-acceptance which, for Danticat, includes her own Haitian identity and American acculturation, often tied to such themes as memory, trauma and love.

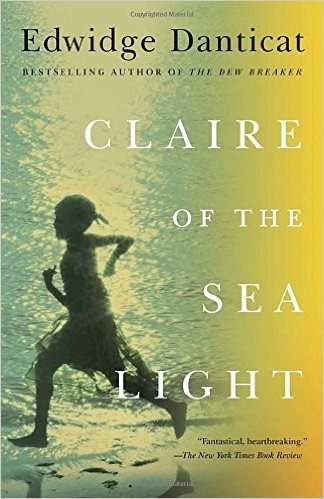

With already seven published novels, including Krik? Krak!; Breath, Eyes, Memory; The Farming of Bones; The Dew Breaker and Claire of the Sea Light, two anthologies and several editorial contributions under her belt, the young writer was featured in the New York Times Magazine as one of "30 under 30" people to watch, and was called one of the "15 Gutsiest Women of the Year" by Jane Magazine.

Danticat-- who was Born in Haiti, raised in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, and is a graduate of Barnard College-- is the recipient of the esteemed MacArthur Fellows Program Genius Grant, the Lila-Wallace Reader's Digest Grant, and the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, just to name few.

On Saturday, April 2, 6:30pm, at The 13th National Black Writers Conference (NBWC) at Medgar Evers College in the Founders Auditorium, Danticat will receive the "Toni Morrison Award," in recognition of her lifetime of exceptional literary work in fiction and memoir. She's excited about being chosen as a recipient of this prestigious award, as NBWC was one of the first places she felt supported and encouraged as a burgeoning, young writer, said Danticat.

"I was so incredibly moved by the amount of talent and inspiration and fellowship [at the conference]; I felt supported; I felt guided. I felt that I could possibly have a future as a writer," said Danticat. "It's hard to express what an incredible honor it is to be part of the conference again, this time as an honoree. The National Black Writers Conference honors the past, present and future of Black writing. I am incredibly honored to be part of that legacy."

In this exclusive interview, leading up to the conference, Danticat sat down with The Brooklyn Reader where she shares a candid, retrospective view of her literary work and her upcoming projects.

-----------*----------

The Brooklyn Reader: The idea of "memory" is a running theme throughout so much of your work and also suggests how tremendous a role it plays in our identities as adults. When we think about the mental illness epidemic we're dealing with increasingly today, it often ties back to memories of past trauma. How do we reconcile this idea of recalling the past while also being able to let it go?

Edwidge Danticat: I think memory is crucial which is why I return to it over and over in my work. We all draw from a particular well when creating-- whether you're a musician or visual artist, there's a source from which you draw, and part of that is memory. Even the way you respond to the present is informed by memory. So it's a foundational force, whether its personal or historical—the common one that we all share that forges our identify. For me, as a writer, memory is not a burden. When I was writing, Breath, Eyes, Memory, I did a lot of research and spoke to a lot of professionals who were dealing with people-- especially women-- who had faced trauma. And one thing they consistently said was that the healing begins when people can tell their stories, express what's happened. I was trying to explore that aspect of a character. They admitted that you may not be able to completely erase a painful memory. But sometimes the questions begs you to go deeper sometimes than the answer. So I see memory as a gift.

BR: In the novel, "The Farming of Bones," you provide a very relatable, personal love story/narrative during the Trujillo era of conflict between the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Where do you see the conflict now between the two countries? Do you feel it is one that has worsened or is on its way to getting better?

ED: Starting with the colonization of the island, the Dominican Republic has a very tense history, which includes common occupation by the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century. But there also have been moments of cooperation. I think the tension is often driven from the top. People amongst themselves generally get along, but often the leadership on both sides of the island have driven these conflicts. So the moments we're seeing now, all of the homeless Dominicans of Haitian descent, there's been a lot of reaction. But a lot of Haitians that have been driven out are being neglected also by the Haitian government, which has not done a good job of re-integrating them. Haiti is one of the greatest trade partners of the D.R., so there are these very close relations that exist. But the deportations and the way they have been carried out and the treatment on the other side has been rather painful and disappointing and very heartbreaking.

BR: We can get a strong sense of how your native country of Haiti has most significantly shaped who you are, as a Caribbean immigrant to America. How would you say Brooklyn has most significantly shaped you?

ED: I can't say enough about how Brooklyn shaped me. Brooklyn was the very first place I landed when I came to the United States, and I felt like it was a really good place to land. I moved there when I was 12 years old, so it played a huge part of my growth as an adolescent. It was amazing to me to see how Haitian families had recreated their lives there. Brooklyn felt like the world to me, because my first impression of the United States was Brooklyn. There were people from all over the world-- people from Puerto Rico, the Caribbean, the Soviet Union, African-Americans-- it was a microcosm of the entire world, which was incredible to see.

BR: In another universe, if you had not pursued writing, what could you see yourself doing?

ED: In my high school year book, the profession I chose was psychiatry. That's what I thought I was going to do, go to medical school, help people, learn their stories. I felt that would be a great way to find out about all of these interesting stories. I've always loved stories. I remember going to the Brooklyn Public Library for the first time-- the main branch-- and getting my library card, and I was so surprised when they said I could take 10 books home for free. I would read through them so fast. I loved that library, the main branch. Reading was my way of escaping, plugging into other basis and leaving behind where I was. I still love reading, I don't have as much time as I did when I was younger. But I think you can never underestimate the value of being a little girl from a family with not much money but having access to books; there's no price you can put on the value of that.

BR: What are you working on currently?

ED: I'm working on a short, non-fiction book, which is in a series of books called, "The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story," which examines how other writers have written about death. Other writers whose works I admire. Almost 2 years ago, my mom passed away, so I've been reading these books to understand how others have lived through this moment.

BR: When you look over your body of work and your years of literary contributions, what are you most proud of?

ED: Sometimes I'm amazed that I have been able to even write these books. I feel incredibly blessed. And looking back at times, it feels like they sort of came through me and had nothing to do with me but that I was a vessel. Being able to get such an award [from The Black Writer's Conference] and in such incredible company [of writers], feels like I'm in a dream. I still feel very much so like I'm in the middle of a journey that I'm encouraged to continue and do better.

*For more information on the National Black Writers Conference, go here.*

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)