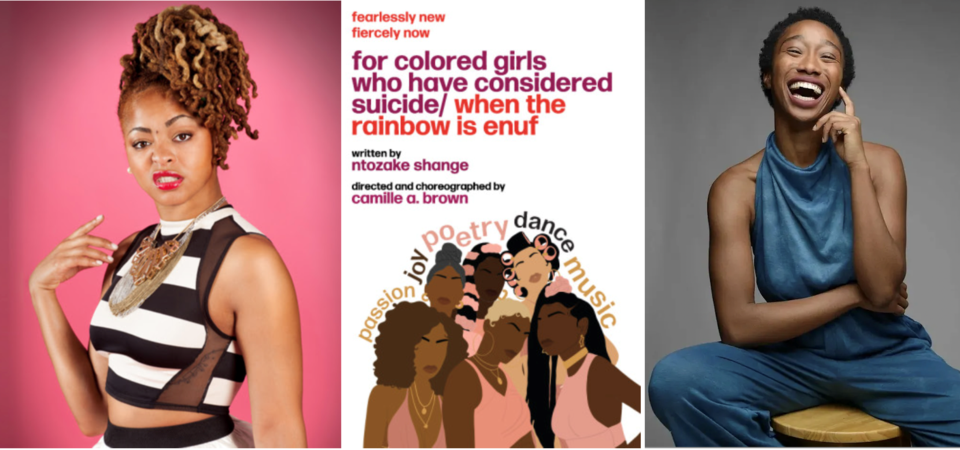

Playwright and poet Ntozake Shange’s Obie Award-winning play For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf currently is on Broadway for the first time since its debut in 1976!

The show's revival opened on April 20, 2022 at the Booth Theatre, in the same location it made its Broadway 46 years ago. Co-produced by Nelle Nugent, Ron Simons and Kenneth Teaton, the show also welcome's the broadway debut of Camille A. Brown as director and choreographer.

For Colored Girls– which the late Shange coined a "choreopoem"– is a series of 20 poetic monologues that tell the stories of seven Black women’s journeys through trauma toward healing. They are the lady in red, lady in orange, lady in yellow, lady in green, lady in blue, lady in brown, and lady in purple.

They arrive to us plucked, it seems, randomly but yet bound by the same burden: navigating racism and sexism in the fight for their womanhood and their peace of mind.

At least two of the play’s actors, Amara Granderson– who plays Lady in Orange– and Tendayi Kuumba– who plays Lady in Brown– are residents of Brooklyn.

Granderson is making her Broadway debut in “for colored girls…” Her training includes an MFA from UC San Diego and a BA degree from Oberlin College. Some of her previous theater credits include Fly at La Jolla Playhouse, Romeo ‘n’ Juliet with Classical Theatre of Harlem and Stick Fly at the Intiman Theater.

Kuumba is an original cast member of Special Tony Award Winning David Byrne's America Utopia on Broadway as well as its World Tour since 2018 and HBO Film adaptation directed by Spike Lee. She is a former touring company member of Urban Bush Women and a longtime collaborator with partner Greg Purnell under the alias UFLYMOTHERSHIP.

Granderson and Kuumba sat down with BK Reader for an intimate discussion around what it means to be a "colored girl," and why, almost 50 years later, the choreopoem continues to resonate for so many women today.

BK Reader: This choreopoem and stage production was written in 1977, almost 50 years ago. It spoke to the experiences of black women at a distinct time in America’s history. How is the play still relevant today?

Tendayi Kuumba: Generational trauma is real. And whether we name it, we can’t deny what has been passed down to us through what our mommies and aunties have gone through. So whether it be from reading the book or experiencing what it is to be a black woman or black girl, there’s always going to be crossing of lines based off of the society we’re living in. I think it’s important to remind ourselves and younger generations that you’re not the first and you’re not the only to experience whatever it is that you’re going through.

So we don’t forget how we’ve had to deal with these things before; how we’ve had these tools for so long to heal ourselves over and over and over again. And sometimes you just need someone else to name it for you so you can access it a little bit clearer, as you continue to mature. And I think there can never be enough space for black women to find themselves and heal.

Amara Granderson: Yes, we are in a completely different era, but I think eras happen in cycles, and we really haven’t changed much in the show at all. We haven’t really updated or modernized the text at all.

Misogynoir is inherent in the way that our society is structured. People are always trying to wash us out of the narrative of the human experience. So I think that this choreopoem that was so beautifully birthed out of Ntozke’s brilliant mind lets you know that, Hey, we are Black women; we are here; we are community; we are the culture. And you can try to disrespect us, but still we rise. Still we’ll be here. And still, it’s resonating with audiences of all generations.

BKR: So, who is Lady in Orange? Describe her to me as if you were telling a friend about another friend.

AG: She’s so energetic. Lady in Orange is such an embracing of new aspects of life that she’s never really experienced before and she’s letting the wonder hit her. Lady in orange chooses joy in the face of adversity and tries to make that joy as contagious as possible. And because she’s there to uplift her sisters, she’s there to uplift herself. And, I just love how joyous she is.

BKR: Who is Lady in Brown?

TK: Lady in Brown is a storyteller, connected to a griot, time-traveler injury. She’s the friend that has tarot cards in her pocket, has her stones with her; constantly remembering childhood memories, might have an Octavia Butler book in her bag. What I’ve learned from her is a form of shapeshifting from what it is to really call to attention not just saying you’re holding space for yourself and other black women, but literally being that container.

BKR: As someone born and raised in Brooklyn, what ways– if any– were you able to draw from your experience as a Brooklyn resident into who you became on stage?

AG: I was born and raised in Brooklyn. But I haven’t lived in Brooklyn in almost a decade until recently. But no matter where I go, I carry myself in the world as “Brooklyn.” I feel there is something very devoid of "B.S." that comes with being from Brooklyn. But the Brooklyn that I see feels like more of a fight to show its heart because of what is happening socially and economically. Brooklyn feels very fleeting to me. And there’s something about the choreopoem structurally that is fleeting; it’s not a linear play. It’s a collection of poems that flows and then goes away and then flows. Ntozake really embraced the fleeting nature of life’s cruelties as well as life’s delights. And I feel like that is something that I’ve been able to embrace as someone who is from Brooklyn, from New York.

BKR: What does this play give us? What do you feel the audience can expect to receive?

AG: So much of the time, we’re told to suppress our emotions. And this piece is an embracing of the nuances of the human experience, of 7 black women embodying completely different things, yet embodying similar things and finding purpose from that individually. Everyone who has come to see the show, I know they feel unearthed in a way that is so unique and so true to not just our production and the incredible vision that Camille A. Brown put this together with, but also, Ntozke’s message, which is so clear: The show kind of bookends itself with “Sing a Black Girl’s song.” It’s a desperate demand that someone please advocate for us. In the play, we’re going through all of these trials and tribulations in life, resulting in the discovery that, Hey, God is within! And it’s not a braggadocious thing in a Kanye sort of way. It’s like, I’m able to love myself fiercely in a world that is ignoring me.

I say all of this to say that when an audience leaves the theater, they feel unearthed, they feel unsettled. It’s a reminder that it’s okay to feel that. It’s okay to feel however you feel. Because that will take you to the next place you need to be, in a more genuine and true way.

TK: I feel like sometimes that there is this invincibility that gets put on black women; that we can take charge and it’s just in our blood. I think it’s something to be recognized, seen and held with care that we are fragile as well. And that we fall apart. And that our falling apart might look different than your falling apart and that’s nothing to be questioned or judged. Everybody’s going through something. You never know what anybody’s going through. I had a man come up to me after the show and tell me how moved he was by just seeing our vulnerability. I think what’s important that men, women of every race get from this work is that, no matter what you’re going through, no matter what you’ve been through, you have the ability to gather yourself, from yourself, from your community.

It’s not always meant for you to comment on everyone’s experience as though it needs input, but to just hold space, witness and appreciate moments that are welcoming for you to see their vulnerability.

For tickets to the Broadway production of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf, go here.