"I put it out of my life, out of my mind. I don't try to remember it or nothing."

For John Robinson, an East New York and Brownsville native, talking about his experience on September 11, 2001, is a rare event.

What he saw that day, and in the 17 days after as he worked doing aid and critical infrastructure work as a City worker at Ground Zero, was akin to a war zone, he says.

Twenty years later, he is still affected by respiratory issues and migraines, a constant remember of a time he tries not to dwell on.

"I might not be in the army or air forces or in the navy. But it was a war that day, we got attacked and we had to defend our country the best way we could: Helping each other."

Robinson, now 58, is one of the five Brooklynites or former-Brooklynites BK Reader spoke to as the world reflects on the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers.

Bed-Stuy's Emily Forsythe was 19 when she got on a bus to New York City from Ohio to help in the aid efforts. Sonya Horton saw two sides to humanity when she walked home to Brooklyn from Manhattan after the attacks. Major B. Bryan Smith climbed rubble to pray for fallen fire fighters. And Sean Edwards, who was living in Red Hook at the time, remembers how the attacks changed the city irrevocably.

For some, it has taken decades to feel ready to reflect on their experience, or to feel their story is "worthy" of being heard. But each marks a moment that New Yorkers who lived in the city at the time will never forget.

John's Story

On September 11, 2001, Robinson was working for the NYC Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). His job that Tuesday was to check the fire hydrants up and down Manhattan were working.

He and his friend Eddie were uptown when they heard on their 2-way radio that an airplane went into the World Trade Center. Soon after, they heard sirens. The pair jumped in their truck, put their lights on, and started heading downtown to the DEP yard at 30 Pike Street.

"We were driving down the FDR, we must have been doing 90 or 100 or more because everyone was going downtown."

When they arrived at the yard, they had the relief of finding Eddie's wife safe nearby, after not being able to get in touch with her. "We hugged, kissed, and then we seen all this white smoke and they told us to head down to the World Trade Center." A wall by the Hudson River had broken, and the DEP workers needed to turn off the mains to stop flooding.

"On our way down there there was another plane hit the second tower," Robinson remembered. "We heard it and then we could see the plane in the building. We thought it was the end of the world."

Soon after, the tower was on fire, and Robinson could see people up above, "holding hands, praying, jumping out the building." They managed to park the car and started running towards them, when the second tower started coming down.

Firefighters were calling for people to get back and get down. Robinson and his colleague hit the ground, and an FDNY firefighter put his coat over them for protection. "If it wasn't for that coat, I don't know...." Robinson said. "All you can hear is debris, glass, screaming, hollering. We must have been on that ground for an hour, better. After everything, silence."

When they got up, the tower had fallen, and everything was covered in white dust. The pair ran to their command center near the West Side Highway and got to work: turning off water mains, loading sand bags where they were needed, and helping those who could be helped.

"I was still in shock but my mind just kept telling me to work, get the water mains cut off so everyone wouldn't be underwater, and so the firemen could have water to put out anything they needed to put out."

Robinson can't forget the cries of people stuck in debris, or the smell. For the next 17 days he worked on the site, sleeping with his colleagues at the yard. They cleared detritus, put up command centers and made sure everyone had running water.

"Every day I worked down there I cried, because it was sad. I never saw nothing like that in my life."

For him, it's still hard to find sense in what happened, 20 years on. He has friends who worked on the site who now suffer from cancers, and he himself suffers from an upper respiratory condition and migraines.

"It's no celebration, no anniversary. Just a terrible bad time for the world at that moment that I just erase."

Emily's Story

On September 11, 2001, Emily Forsythe was a 19-year-old sophomore at Ohio State, studying International Relations. She remembers her roommate walking up to her that day to tell her she had a phone call from her dad. The Twin Towers had been attacked.

She said, even at that age, she feared what the United States' response was going to be. "I thought, tons of people are going to die, we're going to fail at nation building and it's going to be a big mess."

About a week later, she got a call from a friend who had one seat left on a bus to New York to provide aid. Forsythe canceled all her classes and left to New York City the next morning.

When they arrived, the students went to the Red Cross center in the West Village to get their volunteer instructions. While waiting to get their badges, a woman wearing a burkha walked in and joined the line.

"I was in amazement and awe at the strength of people. It was clear that this was somebody who was going to become a pariah. We knew what was coming for her and we knew the strength it took."

Soon after, about 20 volunteers piled into a donated USPS van and headed to Ground Zero. She remembers laughing so hard at one of the fellow students who just got his license hitting off the truck's wing mirror, no idea what was about to face them up ahead. "You don't know what life is, we were a bunch of college kids."

Forsythe said, when they got to Ground Zero, everything was covered in dust and people seemed to be moving slowly, especially because the rescue efforts had just been called off.

"Ground Zero was its own universe, it had no time. I remember seeing the destruction, seeing where the building had been. A lot of buildings around looked like they'd been chopped in half, desks coming out of walls, landlines hanging out, reams of computer paper attached to each other. That was everywhere."

The students got to work, moving supplies from a cruise ship to turn the nearby Hilton Hotel into accommodations for first responders and rescue workers. Supporting the first responders was of utmost importance.

"There was an entire floor on the Hilton of volunteer massage therapists, just working on first responders 24 hours a day." She remembers breaking down in tears finding a couple's wedding photo on the roof of the hotel. Spending time talking with people in the elevator. After Forsythe returned home, she said she told her mom and family about the experience, but hasn't really spoken about it since then.

"I felt like I didn't have the right," she reflects. "And it's just heavy."

And although she's lived in New York 10 years, Bed-Stuy four years, she hasn't been able to visit the 9/11 Memorial. Instead, she stays with her memories.

"It's that bizarre balance of life: With tragedy can come transcendence, and when truly the worst part of humanity and the best somehow became concentrated on this one spot of the earth.

"There just is more love in this world than anybody ever expects, and sometimes it's the tragedy that bring that out of us."

Bryan's Story

Major B. Bryan Smith was serving in the Salvation Army Brooklyn Bay Ridge Corps on September 11, 2001. He remembers he was at home in Bay Ridge that day, writing a sermon, when his wife called him to tell him a plane had gone into the World Trade Center.

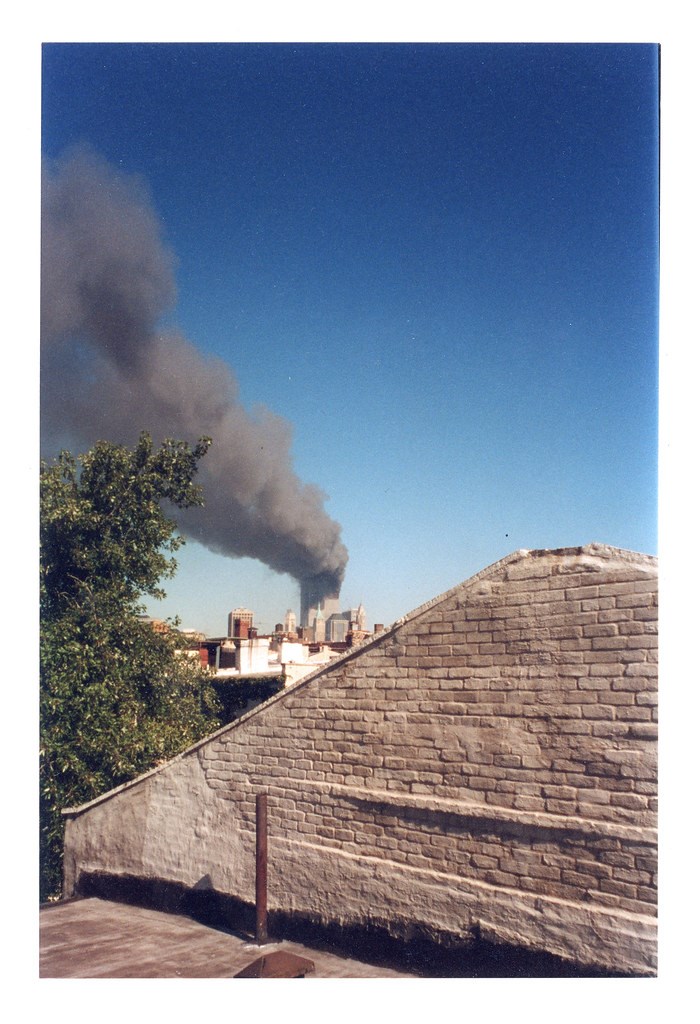

"Where we lived you could see, from the end of the street, the smoke coming up from the towers."

Smith and his wife went to pick up their children from school. There, a woman told him her son was on a floor of one of the towers, and asked if he knew any updates. "From what I understand, that part of the building was gone," he recalled.

Soon afterwards, the Salvation Army had a request to go down to the Lutheran Medical Center to support doctors and nurses who had prepared gurneys outside, expecting a great number of survivors to look after. However, it was soon determined that people would not be coming. "That was a difficult situation for everyone involved."

He remembers going to the Kmart at Sheepshead Bay with a list of things needed for the workers at Ground Zero, and was told to take whatever he wanted for free.

On September 13, he and other Salvation Army members took a van down to Ground Zero. Smith remembers being the only vehicle on the Brooklyn Bridge. When they arrived, he could still smell the jet fuel. The rubble was smouldering.

The next day, the Salvation Army returned with more resources. Volunteers were cooking breakfast for the firefighters, and first responders had come from around the country to help. Their cities of origin were painted in the dust.

While Smith was handing out food to rescue workers, he was approached by a man with a beard who asked if he was a chaplain. They had found two bodies of firefighters in the rubble, and wanted him to do last rites.

While the Salvation Army does not do last rites, Smith knew he could pray for the lost and console the bereaved. He followed the man to the communications center at the bottom of the dig, and then began to be led up into the rubble.

"We walked on ladders that they'd laid on top of the debris, I had two firefighters in the front and two in the back. We climbed those ladders and got to the top and there was a lieutenant with the Fire Department up there, and about 40 firefighters still digging, working with chainsaws."

"There was an explosion while we were up there and I kind of looked back and the Lieutenant said, 'If this starts to move we'll have to ride it down.'"

The firefighters brought the first person to Smith, and he begun to pray.

"I put one hand in the air and another on the bag, and just prayed, 'Well done, good and faithful servant, thank God and may God comfort the family...'

"About thirty workers all had their helmets off, standing solemnly."

About 15 minute later, the other person's body was found and Smith prayed again.

He says the hardest part for him at the time was experiencing that devastation, and then turning around to see things that were "normal," like attending a two-year-old's birthday party soon after.

"I can understand the idea of not forgetting, but I just want people to — not forget — but not dwell on evil and the things that took place.

"Every year on 9/11 we were given these pins, and I would put them on my uniform just on that day, just to remember what we were able to do, spiritually significant things for people. I'm glad I was able to be there for that."

Sean's Story

On September 11, 2001, Sean Edwards was in between apartments, crashing with friends above Lillies Bar in Red Hook. That morning, he remembers someone coming in to say a plane had hit the Twin Towers.

The Red Hook apartment looked directly over the East River to the Financial District.

"We went up on the the roof and one of the towers is in flames, smoking. I went downstairs to text my mom and then another plane hit.

"It went from, 'What a tragedy a plane has hit a building, it must be an unfortunate accident,' to, 'New York is under attack, there's more planes, and all these planes are aiming for New York.' I was in a state of shock."

Prior to the attacks, Edwards remembers New York had a light feeling.

"It was just wonderful, it did feel like, in 2001, like New York was really on the ups, it felt like a time when New York was sort of cheap again, and popping. Then that happened."

For weeks afterwards, there was the smell of metal in the air. Ash from the towers spread a 20 block radius. "People were in shock. There was definitely a sense of mourning."

The event also marked a move into a new sort of patriotism in the city. Edwards remembers "kids from the projects waving huge American flags" and seeing a man on the subway with hateful anti-Muslim sentiments painted on his jacket, with nobody batting an eyelid.

"I don't know how anyone in the Muslim community dealt with that, because it was so brutal that any defense of the Muslim community led to, 'What are you? A f***ing terrorist?'

"You could see the pain in people's eyes who had a store on your corner. It was a really, really brutal sort of hate."

While he remembers New Yorkers approaching the situation with love after the attacks, state and media reports quickly reshaped the narrative.

"A couple of days after, most of New York was like, 'Hey, we should bomb Afghanistan with love or books or whatever.' But that sentiment got twisted quick."

In the weeks after, he remembers the sadness, crying, attending fundraisers at Lillies for bereaved families, some of them the families of Red Hook firefighters who rushed across the bridge to help.

Reflecting 20 years later, Edwards said that day marked the start of a dark descent into American brutality, both at home and overseas.

"There's become a weird political angle to this this thing, justifying the surveillance of Americans, and what Muslims do, and what our response has been. Justifying war.

"What have we done in response to it? What have we created this country to be? An abomination of endless war or surveillance culture, of accepting right wing policy at every turn. An insidious tyranny."

Sonya's Story

Twenty years ago, Sonya Horton was living in Bed-Stuy and working at an insurance firm in Midtown. As she looks back today, the Christian Minister's memories of September 11, 2001, reflect two sides of humanity.

Horton — who was born and raised in Brownsville — says she remembers the husband of a co-worker phoned to say something was happening. The office crowded around a small TV in the kitchen and "watched what everybody watched:" the first plane hitting the north tower, a second plane hitting the south tower less than an hour later.

She and her co-workers didn't know whether they should stay at the office or go home — the trains were suspended. But about 12:00pm she decided to start making her way back to Bed-Stuy. At the time, she was wearing four inch heels, ("that's all I wore!") and remembers walking downtown to cross the Manhattan Bridge, her feet on fire.

When she saw a shop selling flip-flops, she was elated. Until she realized the sandals that normally cost $1 were suddenly selling for $30.

"It showed me that's America, too. We do unity in the time of trial, but we also have this ugly part of us as humans, we don't empathize and we take advantage of a situation if we can."

She grabbed a pair of flip flops that turned out to be too small — her heel hung over the back — and proceeded over the Manhattan Bridge. With her that day was a co-worker who would go on to become one of Horton's best friends.

As they began over the bridge he, a Hasidic Jew, and she, a Christian, began to pray, side by side.

"I'm this Black girl from Brownsville and he's this highly Hasidic man, and he was praying his prayers in Yiddish, I was praying my prayers, we're both praying very loud, and at the end of the day we were praying for the same thing. It doesn't matter what your religion or culture is, these type of events unite you no matter what."

Horton remembers there were no trains running, but the bridge was shaking as though there were, due to the number of people "walking over in soot and dirt, some of their clothing missing, one shoe, the pocket book broken, old, young just trying to get into Brooklyn."

Twenty years on, Horton's fear is, despite the promise to "Never Forget," that we are forgetting.

"My daughter is 8 and I haven't really talked to her about it," she said.

"It's a strange and sad thought for me. I don't think it's something we're talking about. A lot of things have happened in the last 20 years, and we're just forgetting."