From the Column, "The Art of Seeing"

My father died on February 24, 2020. He was ninety-six years old. He had a troublesome heart and difficulty maintaining his balance. In his last years he was best described by the words of the old adage, " nothing but skin and bone." He died in his sleep, lying next to his wife-- my mother—a marriage of sixty-five years.

My mom and I went to work arranging a military memorial and internment that was to have been held a month after my dad's passing at Miramar National Cemetery in San Diego, California. A cremation was arranged, invitations sent out, caterers contacted, obituary placed. We expected fifty or so mourners, not a bad turn out for a man over nine decades old.

The Covid-19 pandemic obviously intervened. She and I agreed it best to delay the event, as many thousands of others have had to do burying their loved ones. In the meantime, the words I planned to share at the ceremony have continued to circle in my head. And every day, new memories of my dad rise up, clamoring to be included. In hopes of stemming this wild rush of recollections, I am putting some of these thoughts on paper. Perhaps I will then be allowed to enjoy (or wallow in) remembrances of my dad at a more measured pace.

The last time I saw my father was less than two months before he died. I had flown out to San Diego from New York for the holidays. Our hellos had, over the years, grown increasingly awkward. He did not like to be touched. Contact with anything was physically painful; the slightest pressure made him wince and more often than not, raised a bruise. He and I had worked out an acceptable handshake, a gentle clutch, palm barely touching palm.

I drove from my hotel to my parent's apartment. I came in and hugged my mom. I then went to the couch where my dad was sitting and reached down to take his hand. He smiled up at me and then struggled to hoist himself up off the sofa and then shift his weight over onto the aluminum walker posted next to him. Once he was upright and balanced, he opened his arms to embrace me. Amazed, I leaned forward and we lightly tapped one another on the back. There was so little left of him. A week later when I left to fly back to New York, this scene was repeated, only this time as we hugged he whispered a hoarse, "I love you."

I could probably count on my ten fingers the other times he had said those words to me.

My dad was not an overtly spiritual man. Any sort of God-doctrine he might have cleaved to was close-held. He specifically requested that we have no religious service for him. Maybe he had some kind of belief or faith which gave him solace when he contemplated his death. If so, it was a faith my mom and I didn't know much about.

We did know that Bill Milton liked to have the proof of things in front of him.

The facts, ma'am. Just the facts.

He had faith in equations which rendered precise answers.

He had faith that certain chemical compounds in combination would yield exact outcomes.

He had faith that with enough tinkering he could make our car's engine roar.

He had faith when he measured and decisively cut lumber, he could create a desk or a table or a chair.

Photo: Boldmethod.com

I have always thought of faith as belief in something which cannot be seen or proven. But then, my father and I had diverged--sometimes acrimoniously--on many subjects over the years.

I know my dad liked the idea of a military internment here at Miramar which makes sense. Much of his life was shaped directly or indirectly by the American military: first as a pilot in World War 2 and then again during his twenty-five years working on government contracts at Lockheed Space and Missiles Corporation.

My dad was raised Catholic. He attended a parochial elementary school back in his birth city of Buffalo New York. After his family moved to San Diego, he went to public junior and high school. Much later, after the war, Bill returned to a Catholic education at the Jesuit-run Gonzaga University in Washington State where he earned his degree in Engineering.

I don't know what religion my biological father and his people favored; Bill and my mom married when I was a toddler.

I do know that our new family of three rarely attended church.

Both of my dad's parents, Bill and Ethel, were what I would call 'serious' Catholics; they attended church every Sunday without exception. They were to be found sitting in the pews for every religious Holiday. There was a picture of the current Pope hanging in their dining room. Meat was avoided on Fridays; fish sticks and with a store-bought jar of tartar sauce were served instead.

On weekends every couple of months, my parents and I would drive down to San Diego from San Jose. And whether out of guilt or respect, Sunday on those visits meant church for all of us. And that held true when my grandparents drove north to stay with us; suddenly an early-morning shower and a suit and tie were on my Sunday to-do list.

I don't remember dad ever specifically telling me not to mention to my grandparents that church-going wasn't a usual event in our household when they weren't around. Yet I felt the excitement in selling the idea that we were as equally committed to the Catholic Church as my grandparents were. I would say the name "Kennedy" loudly in public spaces and learned enough of the Latin Mass to mouth my responses with a certain je ne sais quoi.

When and why my dad jettisoned his Catholic upbringing, I was never sure. Whatever attachment he had to the Church was definitely on the way out when I was still very young.

Even so, when I was eight or nine years old, one of my parents had purchased--or perhaps I had been given-- a new edition of the Catholic Bible. This was not just any old Bible. This was an illustrated Bible. It still retained all the usual text, from the endless "begats" of Genesis right on through to the hellfire of Revelations.

Photo: bing.com

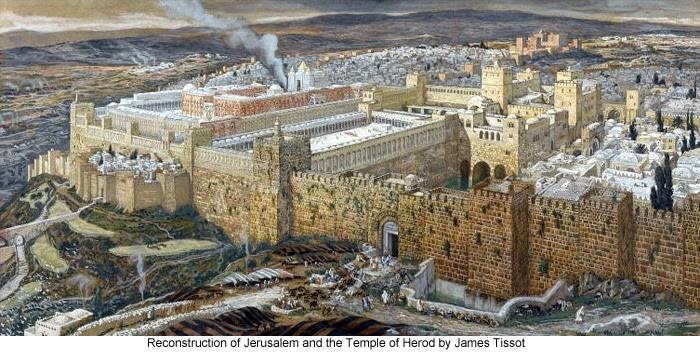

But it also had pages and pages dedicated to photographs of Biblical sites as they look in modern times in tandem with an artist's recreation of the same sites at their prime; the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the temple at Luxor, the city of Jerusalem at the time of Herod.

On Sunday evenings after we had watched The Ed Sullivan Show, my Mom and Dad would come into my room after I had gotten into bed. My Dad would pull up my desk chair on one side and my Mom would perch on my bed opposite him. And he would commence reading.

"In the beginning, God created "

Those half hours of reading had a calming effect on me. I was still chubby and was teasing-fodder from some of the neighborhood "big kids." Each Monday brought on yet another possibility for a new round of humiliation. Sundays found me already head-achy, anticipating all that might befall me the next day.

It wasn't the text my Dad read aloud that eased me. I questioned every turn of the material he shared. An apple He knew would be eaten? A man who lived in the belly of a whale? An ocean which parted long enough to allow Israelite hordes to march through? Even then, Bible stories serving as anything but metaphor strained at my credulity. Bill didn't disagree with my arguments but read on anyway, determined, I imagine, to give me some sort of spiritual first-rung footing, Catholicism as good a place to start as any.

What really caught my interest and distracted me from my fears of the new week were the illustrations and photographs. I poured over them. I went to the library and found other books with more recreations of scenes from ancient times. I found myself seduced into wild historic imaginings; seeing myself on the prow of a Phoenician galley, wandering the halls of the great library in Alexandria, or being the artist creating the glazed tiles which decorated the East Stairs of the Apadana at Persepolis.

Those illustrations my father showed me created an important cornerstone in my life. I developed an absolute passion for history and for this alone I owe him a great debt of gratitude. This fascination has stayed with me all my life and given me countless hours of reflection and speculation as well as a home library filled with books and cherished artifacts which reflect this early-awakened interest.

Which brings me back to the question of my dad's faith.

I wonder now if perhaps his faith--that ephemeral conviction to things we can't see or prove-- was best expressed in his belief in me. Yes, we did engage in almost weekly skirmishes which sometimes blew up into major battles. Causes for these hostilities ranged from me loudly trumpeting my pacifist views on the war in Vietnam to my dad's disapproval over the length of my hair.

"My house, my rules," was his escape clause if ever I cornered him in our confrontations.

Still, he paid for piano lessons to introduce me to "real" music, as opposed to that "crazy Mick Jagger stuff." He bought an Encyclopedia Britannica from to door to door salesman and paid it off monthly for a year in hopes of broadening my horizons. My grandparents gave me my first typewriter, a manual, and my dad made sure I learned how to use it. He fashioned for me an enormous desk at which I spent the next ten years learning state and river names, writing essays, memorizing lines, conjugating Latin verbs.

Whatever our differences, he sought to provide me with a broad moral and intellectual grounding. He kept me fed and healthy. He endeavored to keep me as much out of my own way as possible.

Yes, there was friction between us right up to the end. Recently, upon learning that I am a Zen meditator his response was a dismissive, "Why would you want to waste your time on that?"

And yet, that feeble hug and murmured "I love you" erased all of the guilty verdicts I had delivered against him in the courtroom of my mind. In that single moment, he got an eternal "Get Out of Jail" card.

I love you.

Bill Milton's faith in me is a big part of why I can be here today sharing with you about Bill Milton.

I don't know what happens when we die. Perhaps from wherever my dad now sits, he also aches for this denouement--words by which matters are explained and hopefully resolved—so he might move on more easily towards whatever.

If so, may these words help him along on his journey.