"The Art of Seeing"

The happiest people I know are people who don't even think about being happy. They just try to be good neighbors. And then happiness sort of sneaks in the back window while they are doing good.

~Harold S. Kushner

I hadn't considered what it took to be a good neighbor for years. Living in New York doesn't always encourage acting on that particular sort of reflection. We New Yorkers twist and whirl through our days—like millions of dust devils— mindlessly energized without much time left over for one of the simplest of human connections.

I was born and raised in California. We actually saw our neighbors, day in and day out. We'd see them trudging down the driveway to get their newspaper, or putting out garbage cans, or picking up the mail from their street-side mailbox.

We'd see them in their garages—a pair of overall-ed legs sticking out from under the car—as they tinkered on their engines; or out in the yard mowing the lawn, trimming up a bush. We borrowed cups of sugar, feigned deafness to the occasional late night raised and angry voices, sent condolence notes in times of loss.

Neighborly traditions were easily upheld with all of that casual contact. Neighbors were people who could be trusted. They were a courteous and a friendly source of help when help was needed. They were people who could be counted on, people who cared--and all of this simply because we were all neighbors.

Neighborly traditions were easily upheld with all of that casual contact. Neighbors were people who could be trusted. They were a courteous and a friendly source of help when help was needed. They were people who could be counted on, people who cared--and all of this simply because we were all neighbors.

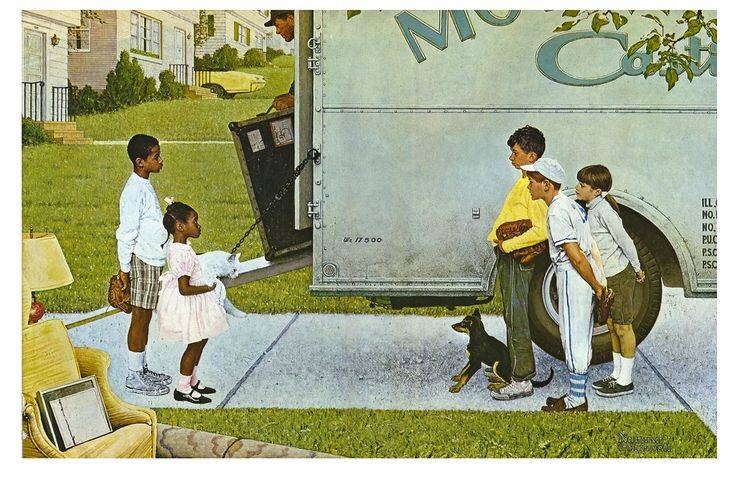

I know I am painting a sort of Norman Rockwell beatified picture of rural and small town American neighborhood behavior. Still, I would venture to guess that much of what I've recalled is truer than not, for many of us.

Here in New York, I live in a ten-story tall building. (See my piece in The New York Times Times, ("Dowager on the Rise," January 2018)

All brick and granite, it was built at the beginning of the last century and has a kind of formidability about it that doesn't smile and say "I'm home" as much as it bellows out, "I'm still here!" I'm not sure I would recognize all my neighbors and the ones I do know took me decades to learn their names. In most cases, our most intimate contact is a hurried "Hi!" when we scurry by one another in the cool hush of our vast wood-paneled lobby.

Recently, I had my left hip replaced.

We help, and we are helped. And in that exchange lies a kind of happiness. That is the art of being a neighbor.

I was healing fine from the surgery—off the walker and weaning myself off the cane—when late one night, I felt a sharp 'pop' as I turned in bed. Pain sizzled up and down my leg. Much as I didn't want to, I knew I was going to have to go to an emergency room to make sure I hadn't dislocated the new hip.

The problem was, this new pain was so intense that I could barely support myself on either the cane or the walker I had brought home with me from the hospital.

I would need to find a wheelchair. I refused to entertain the idea of calling for an ambulance. I fretted that its shrieking arrival and flashing lights would disturb the other people in my building. I didn't want to make a fuss.

I was left with only one choice: I had to reach out to a neighbor.

I called a woman I am acquainted with down on the first floor (I'm up on the fourth) and left a message. Almost immediately, she returned my call. "I'm out of town. I'm so sorry about your news but I am so glad you called me. We don't have a wheelchair but here are the phone numbers of people I know in the building. Try them." I thankfully took the numbers down. Four phone calls later, I had located a wheelchair.

(As it worked out, I had simply popped an internal suture.)

I was surprised at how difficult it was for me to make that initial phone call. It was, after all, almost midnight. I would wake someone up. I was being intrusive. I was being a bother. But once I had broken the ice with that first call, the memories of all the easy assumptions of suburban neighborliness began to awaken in me.

How would I feel, I wondered, if someone in my building called me late at night for help? What if one of these people I hardly knew who lived above and below me woke me up and needed a favor from me? And I can say with near certainty I'd be quite pleased to be given the opportunity to help them out. Oh sure, I'd probably be grouchy at first, but glad later, upon reflection, that I had been able to lend a helping hand.

Proximity creates a kind of responsibility, not necessarily quite friendship but a kind of kinship that requires attention when attention is asked for.

We help, and we are helped. And in that exchange lies a kind of happiness. That is the art of being a neighbor.

In New York City and its boroughs where our lives can be so cordoned off from others, we don't often have the chance to flex our "good neighbor" muscle. That muscle exists within us, near the heart, attuned to many things including—apparently--late night phone calls.

Sometimes the call will be about a wheelchair.

And sometimes, it will simply be, " may I borrow a cup of sugar?"