At just 9 years old, Brooklyn human rights activist Jacqueline Murekatete lived through one of the most brutal campaigns of violence in history, the Rwandan Genocide.

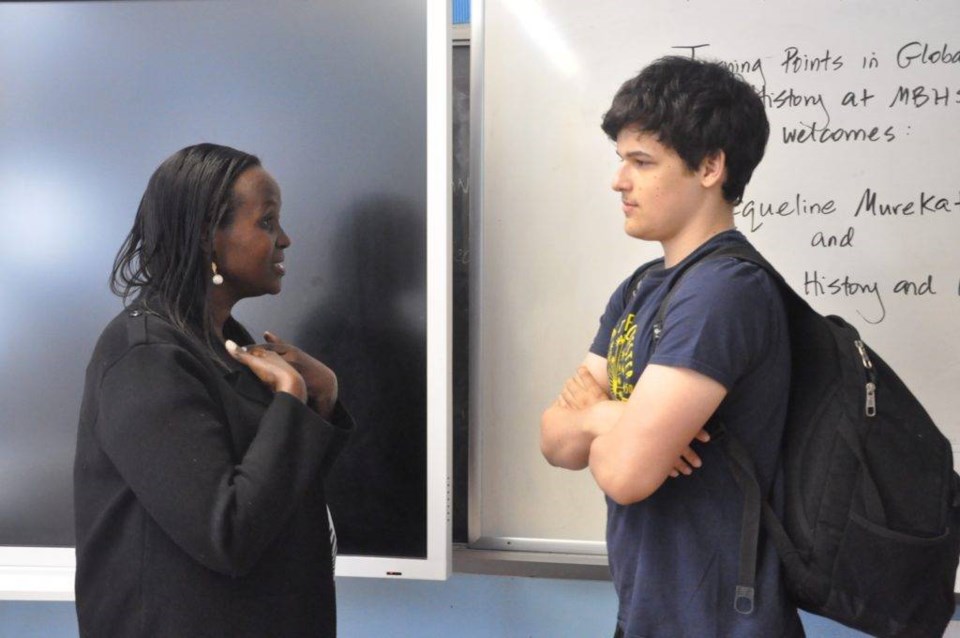

In recognition of the genocide's 25th anniversary, Murekatete visited Brooklyn Millenium High School where she spoke to 12th graders about the dangers of racial bias, scapegoating and hate.

"People don't just wake up one day and decide to kill their neighbors," Murekatete said. "By the time the genocide began, physical preparation and indoctrination had already taken place, so when the government came on the radio and said, 'It's time to kill Tutsis,' a lot of Hutus did not hesitate."

During the 100 days of mass murder, which began on April 6, 1994, an estimated 800,000 people were killed. Civilian members of the Hutu ethnic majority turned against their Tutsi neighbors, wiping out entire families and approximately 70 percent of Rwanda's Tutsi population. When the killing finally stopped, survivors like Murekatete scattered across the globe.

Murekatete was in her grandmother's village at the start of the genocide, and because of roadblocks, was unable to return to the village of her parents and siblings. She fled with her grandmother to a nearby county office, where hundreds of Tutsis believed the local government would protect them. They were not so fortunate.

"Hutu neighbors began coming to that county office armed with clubs and machetes, screaming that Tutsis were cockroaches and deserved to be exterminated," she said. "I witnessed many killings of my relatives."

With the help of an uncle, Murekatete and her grandmother escaped in the back of an ambulance. They were taken in by a Hutu family, but after men broke into the home and threatened them with bloody machetes, were forced to leave.

Murekatete's grandmother heard about an orphanage where two Italian priests were sheltering Tutsi children. She sent Murekatete to the orphanage and promised to come for her in a few days.

"In my young mind I actually believed her," said Murekatete. "But that ended up being the last time I saw my grandmother. After the genocide, I learned she was killed shortly after."

Murekatete spent the remainder of the genocide at the orphanage, where armed Hutu men periodically broke in and threatened to kill the Tutsi children. The priests bribed the men with money to save the children, and once the money ran out, with food.

Murekatete likes to highlight the role of the priests in her story, and the others who helped her. She calls these people "upstanders," and hopes students will be inspired by their brave acts. Thanks to their help, Murekatete survived the genocide. Sadly, her parents, siblings and most of her extended family did not.

"My Hutu neighbors took them to a nearby river, where they butchered them with machetes and threw their bodies in the river," Murekatete said. "Their only crime was being Tutsis, and their government believed that was a crime deserving of death."

In 1995, a year after the genocide, Murekatete was brought to the U.S. by an uncle. They moved to Queens where she attended Martin Van Buren High School. There, she met Holocaust survivor David Gewirtzman, who came to speak to her class. Gewirtzman became Murekatete's friend and mentor, and they began speaking together in 2001 when she was sixteen.

Murekatete earned a B.A. in political science from NYU, then attended Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. After practicing law for a few years, she founded the Genocide Survivors Foundation, a nonprofit supporting survivors and educating the public to prevent future atrocities.

With the educational nonprofit Facing History and Ourselves, Murekatete travels to schools and tells her story of loss and survival to young people. She hopes that the students will be able to relate to her story, apply it to their own lives and to our current political climate.

"We've heard of Mexicans and Central Americans coming to this country and being called invaders, or animals. What do you do with a cockroach? You squash it. What do you do with invaders? You fight them," she said. "So when they hear these things, I want them to know that some kind of an alarm should be going off in their mind, and they need to speak up."