In his address to the City on February 28, Mayor Bill de Blasio outlined how the sheer intensity of the homelessness problem in New York City is further exacerbated by a shift in demographics of homeless families— now seventy percent of the shelter population .

More importantly, according to the report he released following the press conference, Turning the Tide on Homelessness in New York City, "Among families with children in shelters, more than one-third include a family member who is employed." This debunks the notion that homelessness is reserved for the unemployed.

The major forces driving New York City's current wave of homelessness are the rising cost of living and the lack of affordable housing. According to the report, for at least one million of the low-income residents of New York City, only 500,000 apartments are affordable. This means that at least half of the families are rent-burdened, paying more than thirty percent of their income on rent. Combined with income volatility and little savings, rent-burdened families are particularly vulnerable to homelessness-- it takes but just one crisis e.g. loss of a job, sickness of a child or a significant raise in rent.

The same report also showed that, contrary to some public belief, the homeless also are not transients unable to find shelter. In fact, amongst those housed in shelters with a recent address outside the city, almost all of them are returning to New York after unsuccessful attempts to build a life somewhere else.

For example, in the first half of 2016, out of the total 7,329 families who applied for shelter, only 126 families did not have an easily identified prior address in New York City. The vast majority of the families who applied for shelter were originally from New York City. Returning residents account for a sizable percentage of those New Yorkers who find themselves trapped in homeless shelters nowadays.

So, what is driving this pattern of migration and reentry so prevalent amongst New York City's low-income residents?

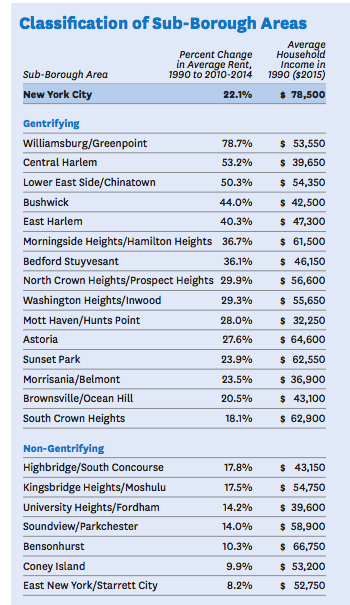

Answers to those questions can be found in the wave of hyper-gentrification taking place across the city, particularly in Brooklyn.

Hannah Hutton is an advocate working with Partnership for the Homeless's Family Resource Center in East New York. The common scenario she witnesses during the course of her work, she says, is a single mother with children being priced out by her landlord yet without the legal representation to defend herself in Housing Court thus forming holdover cases. In holdover cases, tenants do not show a history of non-payment. Also in these cases, landlords do not present reasons for eviction other than significant rent raise once a lease expires.

Hutton shares the story of one recent holdover case in which a single mother with three children has come to the Family Resource Center for help. The mother as evicted in early 2016 after her landlord raised her rent. Although the mother worked two jobs at minimum wages to support the family she was unable to afford the rent increase. After months of searching for a new place to live, she still did not have sufficient means— unable to pay security deposit, first and last month rents all at once— to secure new housing for her family. As a result, she resorted to the shelter system and was placed in the Bronx. Her oldest child was five years old at the time, attending kindergarten in East New York, which required daily commuting from the Bronx. In the end, she couldn't keep balance between work and family duties and lost both of her jobs.

Later in 2016, Family Resource Center connected the young mother with CityFEPS, a program that provides monthly rental subsidy for eligible families, in her case, $1,515/month for one year. As of December 2016, the young mother finally was able to find an apartment affordable enough for her family... in New Jersey. So she moved out of New York City.

When asked whether this woman already had a job when she moved to New Jersey, Hutton hesitated for a second and said, "She took a risk. She hoped to find a job before the FEPS subsidy ends."

Herein lies the problem: the bleak prospect of starting a life all over again in a new city with no promise of employment. Once the subsidy runs out and if no employment is secured, these families are back to square one. So they return to the only other place they have ever called home: the city they left.

"It's like a cycle." Hutton said, lifting her arm to draw a circle in the air.

"We had Advantage before," Hutton continued, referring to the Advantage Program, which provided rental subsidy for a period of two years. However, the program was ended in 2012. The Coalition for the Homeless claimed about 25 precent of the families who were returned to the shelter after leaving the program.

This woman's experience Hutton spoke about has become eerily familiar to the pattern of migration within Brooklyn neighborhoods. It begins as an east-to-west migration of families fleeing a neighborhood undergoing gentrification, such as Crown Heights or Bed-Stuy, in and search of more affordable homes farther east into Brooklyn, namely in East Flatbush and East New York.

However gentrification has now moved into East New York, a so-called "non-gentrifying" neighborhood, according to a report released by NYU Furman Center only in 2016.

The de Blasio Administration's East New York Neighborhood Plan, a rezoning directive passed in April 2016 for the commercial revitalization of the area, outlines new laws that allow for the construction of 12- to 14-story apartment buildings over the next two years, including over 1,200 units of affordable housing. Click here for an interactive map of the plan.

Already, there is a construction site slated to become a bank directly across the street from the Family Source Center building on Pennsylvania Avenue. But will the rezoning plan actually create more economic opportunity for those residents who are there currently? (Residents claim that even the "affordable units" are affordable only to middle-income earners). Or will East New York become another Williamsburg, a "hipster" commercial hub where its "economic development" ends up serving only those newcomers who can actually afford the new rents?

The immense uncertainty about what lies ahead over the next five to ten years for East New York-- often seen as the last bastion of open development in Brooklyn-- can leave one feeling hopeless... but also, may just as well lead to some last-minute reprieve: In his East New York Neighborhood Plan, Mayor de Blasio set aside $62 million in FY 2016 for legal assistance for residents who feel they are being illegally pushed out of their homes. In fact, the City is working on a bill that, if passed, would guarantee lawyers for any low-income residents facing eviction.

There is no hard data yet on the numbers of people who've lost their homes due to powerlessness in the face of lawyered-up landlords or lost jobs due to random placement. But had the mayor implemented the preventative measures one year earlier, perhaps the young mother in the story might have been able to stay in her home. If he had proposed the communal approach to shelters even one year earlier, perhaps she might have been able to keep her jobs.

It is clear that the mayor's sincere goal is to turn the tide of homelessness in Brooklyn and effectively reverse a trend that, with each passing year, has only increased in speed and voracity. However, the fact remains that even if families are able dodge the fate of eviction, more jobs and a living wage is needed for them to remain in their homes and continue to build a sustainable life.

Only time will tell whether the City's latest efforts will finally stop the hemorrhaging of families out of their homes into shelters... or whether they will serve only as a temporary band-aid over a wound that is far deeper than the eyes can see.

Read the first story in this series, Homeless in Brooklyn: Once a Single Person's Problem, Now a Family Affair.

Read the second story in this series, Homeless in Brooklyn: On Shelters, How Fair is 'Taking a Fair Share?'