By Karen Malpede

Cairo is awash in plastics, the water bottles from which everybody drinks, and worse, cheap knock-off-clothing, sneakers, flip-flops and household items imported from China spread out by peddlers on the streets. Western in design, ill-made by workers in Asia working for starvation wages, they sit waiting to be sold to Cairo's poor.

Twenty years ago when I was last in Cairo and there was a bustling tourist trade; the street markets were of hand-crafted items, perfume oils and hand-blown perfume bottles, pearl in-laid jewelry boxes, Egyptian cotton simple scarves, Arabic books. Now these things are gone from view and it's as if one wanders through a massive, out-door discount mall—piles of t-shirts with logos, and the like. The West has come to Cairo through China. Here is globalization and free trade for the poor. It benefits no one, destroys the old craft-based economy and vastly increases what gets thrown away.

At any given moment in Cairo the traffic comes to a stand-still; cars move bumper to bumper with pedestrians weaving in and out to cross wide boulevards or walking within inches of the vehicles on tiny side streets. The air is a mix of carbon monoxide and desert dust. It's said there are nine working traffic lights. There are no trash baskets. They were put out once by the government but quickly stolen by the poor to be melted down and sold as scrap metal—never to be replaced. The gutters are filled with garbage.

For all the mess, the city fascinates. Its people are kind and gracious, passionate. The well-educated are terribly so, knowledgeable, argumentative, lovely.

There is always time for talk. The few up-scale craft stores sell beautiful pottery designed and made by villagers and elegant textiles hand woven and sewn in Egypt. Several well-known designers have opened ateliers where they train young artisans in pottery, textile design and jewelry making. The old Islamic and older folk designs are wedded to contemporary taste and the results are lovely. But these items are for the well-off, or for us, gathered at the 23rd Cairo International Experimental and Contemporary Theater Festival to bring home.

To understand Cairo today: Imagine, if you can as an American, a state of populist, political euphoria: perhaps the Bernie Sanders campaign when your $27 made a real difference because millions of other people also gave; or, if you've longed for a woman president, think of the promise of this moment; or remember the joy in Brooklyn that accompanied the election of President Obama in 2008, when we poured from our homes to dance on Dekalb Ave. Remember, that is, moments of collective happiness and hope.

Then, think that following upon, let's call them pro-democracy populist movements, Donald Trump more or less steals a close election (as we might say George W. Bush actually did). Trump takes power. Immediately, he begins night raids to deport 11 million immigrants, reinforces "law and order" with crack-downs and even more violent policing of black and brown Americans, subjugates women, out-laws abortion and makes birth control and basic health care hard to come by. Imagine a country in which the Alt-Right racist, gun-carrying bullies are empowered by law and governmental decree to "make America great again". They begin night raids, beatings, shootings, even hangings and violence against anyone deemed "liberal", or of color. Gay marriage is outlawed. There is increased public shaming and taunting of LBGT people, of women, people of color and any white man who empathizes.

In other words, public and private life becomes unbearable; the steady human rights gains we've fought for all our lives unravel before our eyes; the economy crashes and people are afraid. Then, to "save the situation", the CIA and the Pentagon step in: they arrest Trump, his cabinet and millions of his sympathizers, throw them in jail and condemn many to death. As a few of the heavily armed white militia members fight back, they are slaughtered (though, of course, others will survive to shoot and bomb again). The new government is now headed by people once high up in the Bush torture and war regime (Donald Rumsfeld, or the disgraced General David Petraes, for examples).

Anyone who criticizes the new military rule is jailed, without charges, threatened with the death sentence, tortured or killed. All protest is forbidden and protest stops because anyone thought to be criticizing the new military regime which after all saved us from the right-wing fanatics and so deserves our praise, anyone who speaks out for democracy is an enemy of the "growing liberalization government." If you can imagine all of this, you will have some idea of the conundrums of contemporary Egyptian society—which joyously toppled three-decade President Hosni Mubarak in a glorious mass uprising of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, only to fall victim to the Muslim Brotherhood's religious fanaticism, and has been rescued from the imposition of a religious fundamentalist state by what is essentially a military dictatorship.

Imagine, the main industry is tourism, as it is in New York City, but because of the political turmoil tourists stop arriving. Every sector of employment is affected. The economy is in shambles; unemployment is high. The price of food and all necessities is rising. Real estate development has come to a crashing halt. Many of the activists are in jail: think all the Black Lives Matter and Color of Change, the antiwar and climate justice intersecting movements, along with independent journalists. Everyone is afraid to speak out. People talk about "the situation" but in private, only. No public protest is allowed.

Then, imagine the reinstatement, after a five year hiatus during all this turmoil, of an international theater festival with a 23-year proud tradition in Egypt. This is a gathering of cutting-edge artists from many countries of the world chosen by Egyptian professors, critics and artists precisely for the bravery of their work.

Imagine these people performing, socializing, teaching workshops with titles like "Theater in the Time of Jihad" by Pakistani dissident, Sharid Nadeem, or mine, "Writing from the Thinking Heart" to groups of Egyptian students who are free within our workshops to speak their minds and to propose, as happened in mine, plays that capture, critique and envision beyond the current social and political situation. Imagine that artists descend upon Cairo for 10 days, funded by and with the official sanction of the el-Sisi government's Ministry of Culture, imagine Egyptian theater artists, professors and critics, all as warm and hospitable as is Arab culture, engaging openly in debate and discussion, and you will have some idea of the liberating strangeness of my recent stay in Egypt.

There are buses that take the festival participants through the horrific Cairo traffic to 4 plays a night—too many for one person to see, so I focus mainly on the plays from the Middle East. There is free and animated conversation between playwrights and artists from Kenya, Iraq, Egypt, Pakistan, Russia, Chile, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, England, and many other places, including the U.S.—too many interesting people for any of us to get to know. There is a shared sense among all of us, most strangers until these shared moments in Cairo, of our necessary mission as artists to put social critiques of war and tyranny and images of social justice, plus beauty and humor, into the public sphere through our theater art. We are hosted and paid for by the Egyptian government. There are daily publications written by a slew of eager, mainly very young, journalists: interviews with all of us, in-depth coverage of our workshops, descriptions of the performances and plays—and these are handed out free to all of us as well.

It's a privileged bubble that we live in, one of free exchange of idea and art, unusual anywhere—and we are also interacting with Egyptian students and young artists in our workshops; we become facebook friends to keep up the conversation and exchange.

Imagine that the Minister of Culture of the el-Sisi government arrives at the closing night ceremony to bless the festival and to proclaim that art is the antidote to terrorism and that this Festival is being funded for that purpose (although, perhaps, he does not mean, state terrorism). But in any case, we are expected to tell the truth about fundamentalist violence, and to speak out on the stage (many of the plays feature women in the leading roles and tell women's stories) and in our workshops (mine was a majority of women) about gender equality. And I would say that we, this gathering of internationals of all skin hues from most continents, brought here by the Egyptian government—or rather by the academics and critics who convinced the government to reinstate the Festival—hold ourselves to a high standard.

We expect ourselves to see through governmental and official posturing; we expect ourselves to truth-tell about violence whether by state or non-state actors in our home regions. We expect ourselves to counter prevailing narratives like "radial Islamic terrorism". We expect ourselves to speak about the human cost of the wars our own governments promote—and this is especially important if one is an American, for too few people in the Middle East understand that some of us did and do protest American invasions and endless military interventions. We expect ourselves to write our truths and at the same time we know that will suffer for doing so in whatever is our native home—some of us have been in prison (me, included, for antiwar protests), all of us talk about hard it is to do the work we do.

In conversation over lunch with Sitawa Namwalie from Nairobi, we acknowledge not only do we have to write our ecofeminist, anti-violence and corruption, poetic, visionary dramas; we then have to raise the money, hire the theater, direct, perform or gather the actors to perform—and that it never does get any easier. Not in New York for me or in Nairobi for her. And we are among the lucky ones. Shahid Nadeem, from Pakistan, has served prison time for his plays. Many of the artists at the Festival are refugees: from Iraq, primarily, living in Sweden or Jordan and London, and in the case of an actor I have worked with in my play Another Life exposing the U.S. torture program, Abbas Noori Abbood, a new American citizen now living with his Tunisian-French-American wife in Cairo because she does food aid work for the UN.

So many of the people I meet have suffered, and are suffering from the invasion and occupation of Iraq, the Syrian Civil war (a professor from the University of Damascus is present at the festival). She requests a copy by email of an anthology of American and British antiwar plays I edited, Acts of War: Iraq & Afghanistan in Seven Plays. I will send it to her because there is no other way she can see that some playwrights from the West spoke out against the madness. (In Damascus, of course, she is "protected" by the murderous Assad regime.)

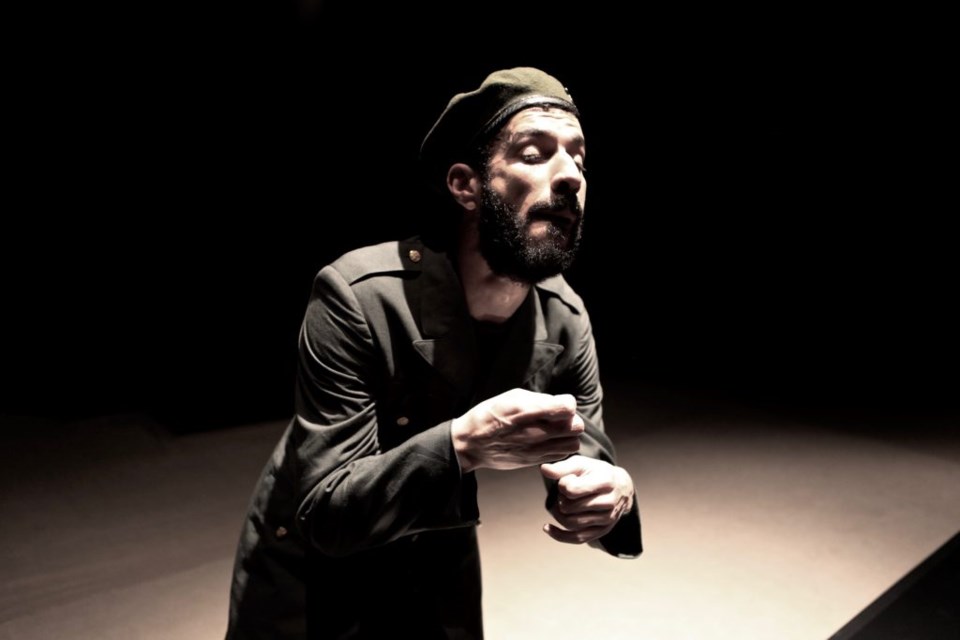

Imagine watching a play, Pillars of Blood, co-created by an Iraqi refugee and his Swedish partner, that physically and viscerally in the body of this extraordinary Iraqi actor, Anmar Taha, reveals the enormous pain of those living under constant threat of violent death. A play beautiful and haunting nevertheless. This play is so relevant to the United States, not only because of our invasion of his country and our infliction of violence on the entire population of Iraq, but also because, in so many ways, that war we started over there has come home again to our hoods, with our incarceration rates, our solitary confinement and other sorts of torture, our attempts to take the land again from the Native American tribes who protect our water for us, to turn dogs on them.

Imagine a theater festival that speaks across boundaries and makes the poverty and suffering of the world's people visible even as the artistry involved gives us beauty, music, laughter, brave characters and, somehow, redemptive plots. Starring at the violence in the Middle East, while being in the Middle East, and sharing so much that is unique but also familiar about the very many different places from which we come is liberating. Imagine that. Imagine that a theater festival proves again and again during its ten-day duration, that we are indeed one people, living on one hot and endangered planet, growing hotter and more endangered even as we share our art.

If only we could live together as we are let do in Cairo, sharing our artistic messages with the Cairo audience and with each other—what a world we might create. What a just and equitable, compassionate world is right here, tangible and touching, despite the contradictions, or in tandem with them. If only, those who see into and see through, who see beyond and see past tyranny, oppression and war, who see what might not yet exist, whose very sight calls the unknown into being, if only we can hold onto to these strange and rare days in Cairo then, a new world is possible of our making.

I ride horse back one early morning with my great friend and major Egyptian theater artist Dalia Basiouny. We take the horses into the Sahara desert. I sit tight on my sure-footed little horse and give him his head, as he gallops over the sand into a desert horizon vast, unknown and liberating. Later, Dalia and I drink tea on a balcony overlooking the pyramids and Sphinx. The next day, Dalia takes a few of us to visit the churches of Coptic Cairo; Egypt itself means Copts, and the Coptic Christians pre-date the Muslims on this land.

The day after, we visit Dalia's organic farm in the desert outside Cairo, pick and eat her dates, mangoes and olives, and talk about the hard financial situation. Her sister and mother, who share breakfast with us, wear the hijab; she does not. Abbas from Iraq is here, and my husband who was a child refugee from Nazi Germany, and Abbas's partner, Muriel, with their 10-month old, Sirine. We worry together about the world "situation", climate change and world hunger. We speak of Muriel's work at the UN, our recent work as dramatists, Abbas's comic video series Bicycle Barbershop in which he as an Iraqi barber cuts American's hair while interviewing them about Donald Trump. It's our art that brought us together originally and the Cairo Theater Festival that brings us close, again, for these few days.

"Tell Americans to come to Egypt," one of the Festival organizers says to me at the closing ceremony. I will gladly give Americans this message. Go to Egypt and experience the kindness and warmth of Arab culture; see the beauty of the past and experience the contradictions of the present moment. We are only frightened of what we do not know. We can only be manipulated through our own fears and ignorance. We are braver than we think—and more creative, too.

And all these strengths are needed now for the world has veered off-course, in large part due to America's on-going wars. It's up to all creative souls to bring us back to sense: to imagine peace and environmental justice. Then, as happened for 10 days at the Cairo Theater Festival, we might use our energies to care for one another, create beauty and truth, and support our fragile earth.