Selma, an epic and compelling contemporary take on Civil Rights history, arrives in movie theaters at the perfect time to chastise a nation which once again, or perhaps, as usual, is in the grip of racist tension. (It is showing on the large screen at BAM's The Harvey through January 16).

Selma, an epic and compelling contemporary take on Civil Rights history, arrives in movie theaters at the perfect time to chastise a nation which once again, or perhaps, as usual, is in the grip of racist tension. (It is showing on the large screen at BAM's The Harvey through January 16).

Made by African-American woman director, Ava DuVernay, the film is a mix of the historical, political and the personal. Some factual liberties have been taken for the purpose of creating an artistic experience that emphasizes the true bravery, courage and commitment of the ordinary and of the famous, each one of them extraordinary, participants in the movement that achieved the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

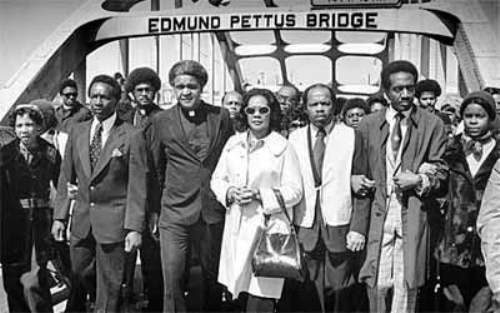

Martin Luther King's wife, Coretta Scott King, plays a defining role and the intricacies of their troubled marriage resolve in the show of unity which is the third and final climactic march from Selma to Montgomery. Coretta marches with Martin, forgiving him his infidelities, at least for the moment, as the movement forgives him the earlier aborted march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge and victoriously reaches Montgomery.

The violence, there is plenty of it, protestors shot or beaten to death, is neither exploited nor sensationalized. The murderous racist hatred in all its viciousness is seen on screen, but focus is pulled by close-ups of the faces of the protestors, their dignity, resolve, their tears and fears and ultimately by their successful battle—waged nonviolently.

Nonviolence, its costs and effectiveness, not only as a moral stance but as a realistic tactic, is the film's recurring theme. King's acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize is juxtaposed at the movie's start with the Birmingham Church bombing—four little girls in their Sunday best are talking about their hair, when all of a sudden The memory of their murders increases the urgency of the movement and its willingness to choose Selma, Alabama, one of the potentially most violent places, with its racist sheriff and white population, to push for voter's rights.

In truth, SNCC and local citizens had been organizing in Selma for several years before King and the SCLC joined and focused national attention there. "You provoke violence," King is told at one point by Johnson's negotiator, how can you say you are nonviolent? But provocation was part and parcel of the strategy. Meeting violence with dignity was logistic; such confrontations revealed to the nation the necessity to change our laws. Malcolm X comes to Selma while King is in jail and meets with Coretta Scott King, saying that while he has softened his violent rhetoric (he would be assassinated in Harlem just weeks later), his presence might serve to remind the public of the alternative to the nonviolent protests.

These brief reflections are not intended as a review of the film. Selma has been enthusiastically reviewed and deserves high praise, for its acting, directing, script and cinematography. Everyone should see this film.

It brought tears to my eyes more than once—tears of pride, as a matter of fact, for the contemporary talents involved, but, more so, for the extraordinary history invoked. Those were amazing times. What Selma dramatizes so well is the relationship to government of a huge and growing social movement pledged to nonviolence. Local governments like Selma's were violently opposed to change but the national administration in Washington understood its inevitability and rightness.

Washington was able to perceive the movement variously as a "commie" threat (J. Edgar Hoover's F.B.I.), as a goad but also, ultimately, as an ally. The Movement would shift public opinion; then legislation could be enacted. For a brief, shining period of ten or so years, "the Sixties," citizens (we were not yet called "consumers") marching in the hundreds, then thousands, and many hundreds of thousands for civil rights and, then, for an end to the Vietnam War (racist itself) not only believed they might be able to do so but actually were able to change public policy in the public interest.

There were bombings, shootings on campuses, assassinations of public leaders, including, of course of Martin Luther King, one year after he linked poverty, the Vietnam War and racism in a famous speech at Riverside Church. But there was also legislation: antipoverty programs, school integration, the Voting Rights Act the film memorializes, and there were political changes, a president, Johnson, who initiated real domestic reforms, then refused to run again for a full second term because of the War, and another, Nixon, elected on a bogus pledge to the end that war who resigned in disgrace, and a war that finally ended in part because of massive unrest at home and within a drafted military.

The country was different in 1974 than it was in 1963, the year of John Kennedy's assassination. But the changes while necessary and real caused a backlash that we, as citizens, have been unable to effectively confront.

It's difficult to imagine, today, a sustained, effective, large nonviolent movement for police and prison reform, eradication of poverty and racism, for climate justice and sustainable energy policies, and against interventionist wars—all necessary, interrelated causes of utmost individual, social and national import—gaining wide-spread traction, becoming a moral beacon and working contentiously but ultimately alongside national government to change priorities, laws and allocation of national wealth.

The largest antiwar march the world ever knew failed to stop the invasion of Iraq; then Barak Obama was elected, in part, because of his opposition to that war—which he, also, despite his claims, has failed to stop, and, perhaps once begun it was unstoppable. We've witnessed and participated in Occupy, and, today, Black Lives Matter movements as galvanizing moments, but we've yet to step into that river of moral imperative for change, swelling from the bottom up to include the poor, the young, the middle-class, the clergy, also the artists and intellectuals.

We lack a sustained nonviolent movement for social and environmental justice that could force the government to take necessary actions, even though for the past eight years we've had in place a more or less receptive administration, at least, as was true of Johnson's, on domestic issues. We lack the gumption and the guts, the sheer persistence of the Civil Rights and the antiwar participants; we lack their sense of moral righteousness and their willingness, or, perhaps, their sense of the inevitability of their personal sacrifice. Though our causes are equally urgent and just. This is why Selma brought tears to my eyes. At the film's end historical footage of the march to Montgomery is interwoven with the fictional footage. To DuVernay and the actors' credit, the same fervor and purity on the historical faces is also to be seen on the faces of their interpreters.

This is why Selma brought tears to my eyes. At the film's end historical footage of the march to Montgomery is interwoven with the fictional footage. To DuVernay and the actors' credit, the same fervor and purity on the historical faces is also to be seen on the faces of their interpreters.

Everyone looks beautifully alive with belief not only in a better world in the making but also in their own inalienable right and duty as citizens of a democracy to take active part: to become creator, witness and recipient of collective change for the national good.